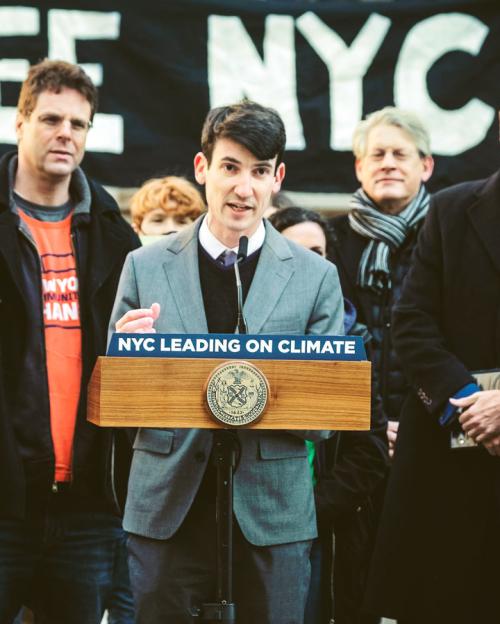

In late December, then-New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a law that will eventually ban the use of natural gas in new buildings in the five boroughs. Among the supporters at the event—held outdoors despite the chill, like so many during COVID—was a prominent staffer who’d helped spearhead it.

As Ben Furnas ’06, then director of the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Sustainability, told the crowd: “This is a historic step toward reaching our carbon neutrality goals and reducing our reliance on fossil fuels.”

The achievement capped Furnas’s eight years in various roles in the de Blasio administration, which also included work on such issues as immigration and traffic safety. But promoting environmental sustainability and staving off climate change are his passions—and now, he’s pursuing those goals at his alma mater.

This semester, he became executive director of the 2030 Project, a new Big Red climate initiative; while he’ll remain based in NYC—he lives in Park Slope, Brooklyn, with his wife and young daughter—he’ll return to the Hill regularly.

An Ithaca native, Furnas double-majored in government and economics; he was active with the student sketch comedy group the Skits and studied abroad at the University of Singapore.

While he holds a law degree from NYU, he has spent the bulk of his career in government policy roles.

He also cites the influence of his parents: his mom, an elementary school music teacher, was involved in opposing the natural gas extraction technique known as fracking, while his dad, a longtime staffer at Cornell’s Mathematics Support Center, instilled a love of nature through regular hikes in the region’s parks and gorges.

How do you answer someone who says, “I believe climate change is real—but as one person, what can I do?”

The problem can feel really large, but there are ways to shift away from fossil fuels toward cleaner alternatives—like electric cars, or switching from a furnace to a heat pump. But a big thing is to support politicians who are dedicated to real change on climate. There’s a temptation to think we can all make our tiny choices and that’ll be enough, but it’s going to take major systemic changes as well.

What are some ways in which you incorporate green practices into your own life?

I have a bike that I like using to get around New York City, and I take the subway and mass transit whenever I can. I try to eat vegetarian and reduce the climate consequences of my food. I’ve been talking to my landlord about shifting away from fossil fuels, but that’s a complicated conversation.

What are you most proud of from your time in NYC government?

One thing is that we entered into an agreement to purchase 100% of the city government’s electricity—about as much as the entire state of Vermont uses each year—from clean and renewable sources. Right now, a lot of the city’s electricity comes from natural gas power plants in the five boroughs—so in addition to helping fight climate change, this will improve air quality, particularly in neighborhoods that have suffered from dirty air for too long.

You also helped pass a law banning new gas hookups. Since people often worry that greener practices will mean lifestyle sacrifices, how can you reassure despondent home chefs?

Cooking is shifting away from natural gas to advanced induction stoves, which are as different from the old electric coils as a flip phone is from an iPhone—more reliable, clean, efficient, and easy to use. Also, there has been a good amount of research on the indoor air quality consequences of gas stoves. This is exactly the type of technological change we’re looking to embrace as we shift away from fossil fuels, and a great example of how taking action on climate can mean other important benefits for human lives.

Your successes in NYC could have propelled you to a position at the federal level. What made you want to head up this new Big Red initiative?

Cornell is uniquely situated to speak to important questions in climate change—whether it’s advancing battery technology or managing dairy farming across Upstate New York. And the University has set some ambitious, thoughtful goals for its own campus; it has been out in front with Lake Source Cooling and Earth Source Heat. Ithaca has similarly ambitious goals, so I think of Cornell as part of the broader community of climate action.

Could you describe the 2030 Project?

It will support climate work across the University, and make it clear that Cornell is mobilizing to support climate action at the local, state, and federal levels, with all the tools of an advanced research university. We’ll be thinking about new technologies we can help develop, new ways of approaching policy—collaborating with faculty and deans to accelerate efforts to put Cornell’s world-class minds, labs, and fields to work to address climate change.

What’s the significance of its name?

At the most recent U.N. conference of global leaders on climate change in Glasgow, Scotland, President Biden and many others referred to 2020–30 as a decisive decade; also, a lot of national and state goals have a 2030 deadline. It represents that this is a limited, but important, stretch of time to mobilize on this issue.

As an undergrad, you did a lot of sketch comedy. Does a sense of humor come in handy when you’re dealing with something so grave?

When I think about the role of humor, it’s part of thinking about, “What are we saving humans for?” It’s so we can live meaningful lives, full of joy and happiness. Also, there are many absurd things across politics and government; sometimes, it’s calming to relish the absurdity.

Overall, how does working in this field inform how you walk through the world?

It gives me a sobering sense of how much work there is to do. Fossil fuels are core aspects of almost every human system. Look at all the cars that have internal combustion engines, every building that has a boiler in it, all the concrete and steel, every piece of plastic, the food we eat—all these things that make a modern, healthy, prosperous life.

The way you describe it sounds so overwhelming.

The great challenge of our time is to maintain these amazing benefits and continue to expand them to more people around the world, while reducing their negative climate consequences. And if it’s done thoughtfully, it can improve other aspects of our lives—cleaning our air, increasing biodiversity, reducing inequity, expanding justice, empowering communities, creating high-quality jobs. It’s exciting, but it’s daunting to think about the work we have to do in the time we have.

On a philosophical level, did your thinking around this intensify when you became a dad?

It’s a cheesy cliché, but it’s genuine. In 2050, my daughter will be 30. It would be totally lovely if, by then, climate change is not something she’s concerned with, because we’ve laid the groundwork for safer, more sustainable systems for her to live in. The universe is vast, but humans have this infinitesimally small amount of space where we can live and flourish. It just makes sense that we’d protect it.

Read the story in Cornellians.