When you consider some of the biggest innovations that have changed public health — pasteurization, disease eradication, water purification — you’ll see behind the scenes an entire network of unsung heroes and heroines, author Steven Johnson says. Not just the inventors or scientists who developed the technology, but the visionaries, evangelists, activists, artists, mothers, milkmaids, pilots, philanthropists, philosophers, politicians and many others, who took the good idea and brought it to fruition.

That collaborative nature of innovation was one of the key messages Johnson delivered during a campus visit Sept. 22, as a guest of the Milstein Program in Technology & Humanity. His visit was also sponsored by the Department of Science and Technology Studies in the College of Arts & Sciences and Cornell’s Masters in Public Health program.

"Steven Johnson is a biographer of change. But I think what makes his work so compelling is that it is, ultimately, about us,” said Austin Bunn, director of the Milstein Program in Ithaca and associate professor and Koenig Jacobson Sesquicentennial Fellow in the Department of Performing and Media Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences, during his introduction of Johnson. “His books tell the story of social, scientific, and technological innovations through people: their ingenuity, mistakes, flurries of insight, dedication and very real sacrifices. This is a fundamentally hopeful and humanist vision of history. In his telling, good ideas, the ones that alter lives and open up the world, have protagonists. And any of us could be one."

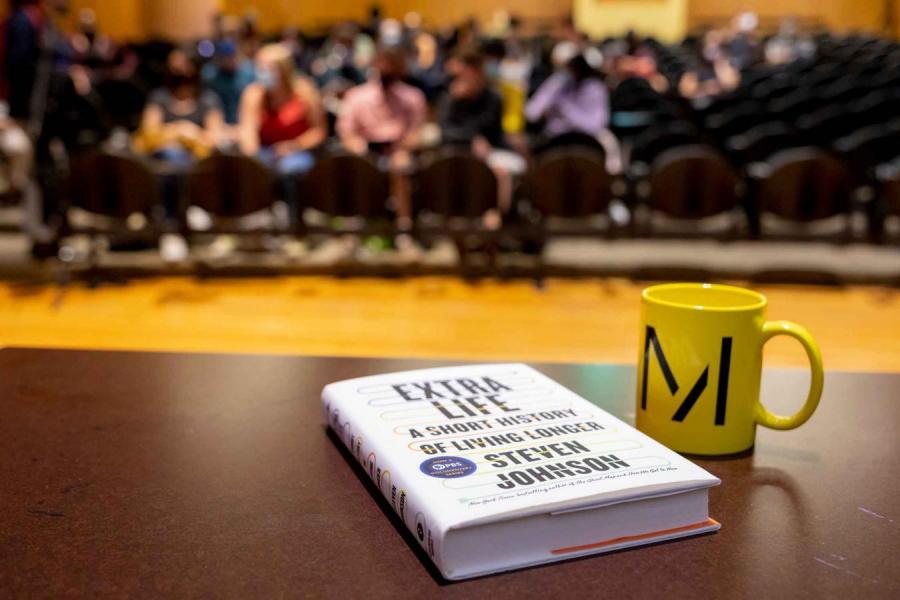

Johnson, author of 13 books including the recent “Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer” gave a public talk and also met with students and faculty during his visit. He is co-host and co-creator of two PBS series, Extra Life, which premiered May 11, and the Emmy-winning PBS/BBC series How We Got to Now from 2014.

In the last 100 years, global life expectancy has doubled, from 35 years to 70 years, Johnson said. But “in a sense the progress is measured in non-events — the smallpox infection you didn’t get at 3, the car accident you didn’t die in because you were wearing a seat belt,” he said. “We have an interesting blind spot to this kind of progress, but pandemics have a tendency of making this kind of invisible progress visible.”

Telling the story of the smallpox vaccine, Johnson explained that although Edward Jenner had the idea of injecting people with small amounts of a similar virus, cowpox, the idea would never have taken off without the earlier efforts of Mary Montagu. A wealthy member of the British elite, Montagu traveled to Turkey where she saw people experimenting successfully with variolation (deliberately injecting someone with a small amount of virus to develop immunity). She had her own children inoculated against smallpox and brought the idea back to England, where the practice spread across the country, then across the world.

“Montagu was not a doctor, not a scientist, not a medical professional or a public health expert, but she was a connector open to new ideas and was able to make the case for these ideas,” Johnson said. “You have people doing amazing things, but you also need to have people out there fighting for these ideas, getting them into circulation, crossing borders, literal geographic borders but also intellectual ones. That role is equally important.

To help smallpox vaccination take off, new needles were invented and refrigeration systems were developed. The world’s experience with smallpox also paved the way in the next century for the creation of organizations like the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control in the U.S., which continue to help make public health campaigns like vaccine rollouts more efficient and effective.

Johnson said similar stories can be found of collaborations to fight famine, to push for the pasteurization of milk and to develop drug safety regulations that led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration.

Looking to the future, Johnson said some of the top health challenges for the coming decades relate to inequality in terms of lifespan and healthspan (how long people are living healthy lives) and to balancing the benefits of gene-editing and anti-aging technologies with ethical considerations.

“We lack an institution capable of wrestling with very complex ethical issues that impact the world,” Johnson said, “so just as we had to invent institutions like the WHO to coordinate change on this level in terms of eradicating smallpox, we may have to do the same thing to think about new medical scientific breakthroughs. That’s a complicated task.”

But Johnson said his research makes him hopeful that society will rise to meet any new health challenges that arise. “We’ve done these hard things before.”