As a primary school student in Japan in the 1950s, Naoki Sakai was made to drink skim milk at lunchtime every day. “It was not tasty, but I could manage to gulp it since I was told it was nourishing and good for health,” Sakai said. He was surprised, years later, to learn that some British friends had also been given the same low-quality American-sourced milk at school.

Sakai now recognizes the American-made global system that “overwhelmed” his youth in Japan as “Pax Americana,” the political, economic, military, intellectual and cultural order of the world sustained by the global hegemony of the United States since the end of World War II.

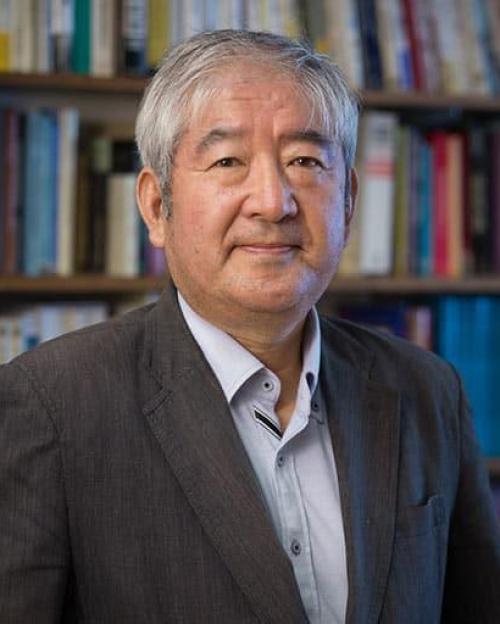

In his new book “The End of Pax Americana: The Loss of Empire and Hikikomori Nationalism,” Sakai, the Distinguished Professor of Asian Studies Emeritus in the College of Arts and Sciences, examines Pax Americana and its lasting effects on Japan, as well as other countries and universities in the phenomenon of “area studies.” In an era when Pax Americana, as a colonial order, is in decline, Sakai sees a new order taking place that dislocates America and Europe (“the West”) from the center of world power.

The book assembles essays Sakai published over a long period, many of which he gave as public lectures since 2000 in places such as Singapore, Leiden, Hong Kong, Leipzig and Kyoto.

American political and cultural power after World War II brought about the end of empire for other once-powerful nations, Sakai said. In the United Kingdom, individuals widely felt the loss of empire for the first time in the 1970s, he said, leading to collective anxiety, anti-immigrant racism and eventually, the withdrawal from the European Union.

“I have witnessed something similar happen in Japan,” Sakai said. “The Japanese were also covertly proud of their imperial status in relation to Asian neighbors.”

Sakai describes a reaction to Japanese loss of empire – a widespread shift toward isolationism – as “hikikomori nationalism;” the term is inspired by the social phenomenon of hikikomori, often translated as “reclusive withdrawal.” Starting in the 1980s, many young people in Japan – up to 2 million – withdrew from social activities to confine themselves to their bedrooms.

“It occurred to me that this social phenomenon of hikikomori was contemporary with the general sociopolitical trends increasingly prominent in Japan at that time,” Sakai said. “Japan’s domestic politics shifted to the right and populist movements gained wide support. It was the period when the Japanese economy began to stagnate and enter a long period of recession.”

Today, Sakai observes Americans perceive a similar loss of empire in their everyday lives. The order of Pax Americana is extremely important to Americans, he said, even though most Americans are not aware of its presence in the world. “Americans take it for granted,” he said.

As a historian, Sakai is pessimistic about repercussions of the twilight of Pax Americana, which he calls “the most sophisticated form of modern colonialism.” He looks to the United Kingdom and the fallout from its exit from the European Union as a forerunner of lost empire.

Although Pax Americana is in deterioration, Sakai said, this order is still an international framework in which we continue to live.

This is evident in universities, he said, where area studies departments center a European-centric view of the world while categorizing knowledge from any other tradition as something other. He wants to free area studies, such as Asian Studies, from “the binary formula of the West and the Rest.”

Sakai is at work on another book, tentatively entitled “Dislocation of the West,” that will provide a large theoretical framework for the issues raised in “The End of Pax Americana.”

This is evident in universities, he said, where area studies departments center a European-centric view of the world while categorizing knowledge from any other tradition as something other. He wants to free area studies, such as Asian Studies, from “the binary formula of the West and the Rest.”

Sakai views area studies as being in crisis as the world continues to shift away from a western-centered view. “I would like to engage in conversation with potential readers who find the Eurocentric orientation upon which modern humanistic sciences have been built unacceptable,” he said.

Here are excerpts from an interview with Sakai.

Question: Would you explain what you mean by “Pax Americana?”

Answer: Just after World War II, I was born in Japan when it was under the Occupation of the United States and its Allies. There I received my education from kindergarten through to college. I never lived in the United States before I joined the graduate school at Chicago towards the end of the 1970s. I did not know the American way of life firsthand until I was in my 30’s, but reflecting upon my early life, the presence of the United States was so overwhelming that it could in no way be overlooked either in the public spheres of life such as national politics and the economy in Japan or in my intimate spheres of life such as my immersion in popular culture and everyday consumerism. Of course, Japan was first under the direct governance of the US, and everywhere inside Japan, I could see things American: American consumer products, Hollywood films, American soldiers walking hand in hand with the so-called “Pan Pan girls” - Japanese women escorting American soldiers, American popular music, special red-light districts for American military personnel, and of course American military bases. First of all, the Japan in which I grew up was undoubtedly an American colony, and its subordinate status did not substantially change even after its independence in 1952. So as one of the colonized population, I experienced Pax Americana most directly. Yet, I hesitate to attribute what I experienced in Pax Americana to Japan alone. In the 1970s and afterwards, I have had opportunities to talk with my friends in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Germany, and I have discovered that we went through so many shared experiences. Pax Americana was a genuinely global phenomenon, and peoples under American governance, Great Britain, South Korea, Germany, Japan and many others actually faced the same or similar things without much awareness.

Yet, it is misleading to say that we found the American presence oppressive. In popular mass media, things American —Hollywood films, Jazz, rock and roll—dominated youth culture. Imports from the US —chocolates, coca cola, and hamburgers (in the late 1960s and the early 1970s McDonalds began to dominate the Japanese market) — were worshipped as the most fashionable among the wide range of consumer products in the fast-growing economy. The American way of life, whose stereotypical images many Japanese learned from American family dramas on TV screen, gradually served as the model to emulate in order to improve and modernize their domestic lifestyles.

Hegemony is a multi-faceted system of consensus in which brutal application of violence, economic exploitation, political persuasion, and aspiration toward some ideals co-exist. It is never a static form of pre-established harmony, but a conglomerate that contains internal contradictions and tensions, so it continues to adapt itself to changing circumstances and new demands. Pax Americana is based upon the global hegemony that the United States created after WWII and, as I have explained, the programs of area studies contributed much to its creation.

Q: The other key term in the title catches my interest: how did you come to include the social phenomenon of hikikomori in a book about international and global relations? Would you like to elaborate?

A: From the 1960s though the 1980s, many American area experts on Japan praised the Japanese accomplishments from the mid-19th century by recognizing Japan as “the only genuinely modern society” in entire Asia. This success in modernization allowed Japan to join the international world as a modern independent nation-state when other Asian countries were colonized by Euro-American and later Japanese powers, and then to behave as a colonial super power from the late 19th century until 1945 when it was defeated by the Allies. Yet, from the 1950s on, thanks to American policies toward East Asia which privileged the remnants of Japanese colonialism within the domestic scene, Japan regained the status of empire in Northeast Asia, in terms of its economic superiority under the protection—summarily called “Confinement Policy”— of American military, economic and political strategies. For several decades, the Japanese were allowed to behave as pseudo-colonizers in East Asia.

When Japan was defeated at the end of WWII, it lost its colonies as well as its status as a colonial empire. But, until the 1990s, the Japanese did not face the reality of their loss of empire. Probably then, for the first time, the Japanese nation had to come to terms with the undeniable reality that they were no longer wealthier, better educated, or more civilized than other Asians by any measure. It was no longer possible to take for granted a variety of colonial prerogatives that they used to enjoy vis-a-vis peoples in East Asia.

By hikikomori nationalism, I wanted to single out a general tendency observable in Japan’s public sphere and national politics. The reason for my adopting “hikikomori” is no more than its isolationist desire and inability to deal with the other (in the Japanese case, with foreigners including Koreans, Chinese and Taiwanese, resident aliens originally from the former colonies of Japan). Just like American counterparts obsessed with erecting a border wall, hikikomori nationalists are keen to abolish any chance of encountering foreigners from neighboring countries in East Asia. Or just like the British counterparts who fantasized about regaining the glory of imperial sovereignty by withdrawing from EU membership, these nationalists imagined that Japan could resurrect its imperial status by refusing to answer to its colonial responsibility.