A pipe organ or an electric guitar: which would you expect – or want – to hear in a church service?

This question mattered a lot to many mainline churches around the turn of the millennium, according to music scholar Deborah Justice, contributing to the so-called Worship Wars, intense aesthetic and theological controversies running through much of white Christian America.

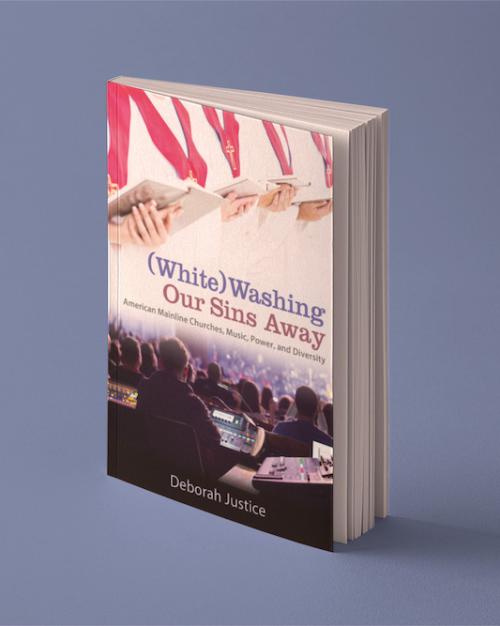

In “(White)Washing Our Sins Away: American Mainline Churches, Music, Power, and Diversity” (SUNY Press, 2022) Justice, managing director of the Cornell Concert Series in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences, analyzes how White American mainline Protestants used the internal musical controversies of the Worship Wars to negotiate their shifting position within the nation’s diversifying religious and sociopolitical ecosystems.

“As mainline Protestants began incorporating amplified, guitar-based Contemporary worship music in an attempt to retain cultural relevance, they negotiated specific pragmatic questions: what instruments to use, what to sing, how to sing it?” writes Justice. “Contemporary worship brought in elements from beyond mainline Protestantism’s historical limits. These sonic elements carried potential overtones of changing social and sacred identities.”

Justice, an ethnomusicologist, was inspired to start this project by her own family history, with a clergyman father and her own deep roots in religion. She was studying ethnomusicology around the time the so-called Worship Wars started in American churches.

“People were getting so passionate about which instruments and musics were being used in services,” she said. While worshippers were getting worked up over electric guitars, music ministers and pastors were quitting or getting fired, and people were switching congregations, she started asking questions.

“Why was it that White Christians were choosing, both consciously and subconsciously, to navigate shifting societal power dynamics through music?” she said. “More broadly, how does the music that we play and sing both reflect and shape our relation to the world?”

Justice conducted some of the research during her dissertation fieldwork in Nashville, Tennessee, where she carried out extensive participant-observation fieldwork, singing and playing in church worship services and doing interviews. To complete the book, she expanded on this core research by conducting further research around the nation.

The project received support from the Hull Memorial Publication Fund in the College of Arts and Sciences. Justice is also the author of “Middle Eastern Music for Hammered Dulcimer” and co-author of “Klezmer for Hammered Dulcimer” (with Pete Rushefsky). She has taught at the Setnor School of Music at Syracuse University.