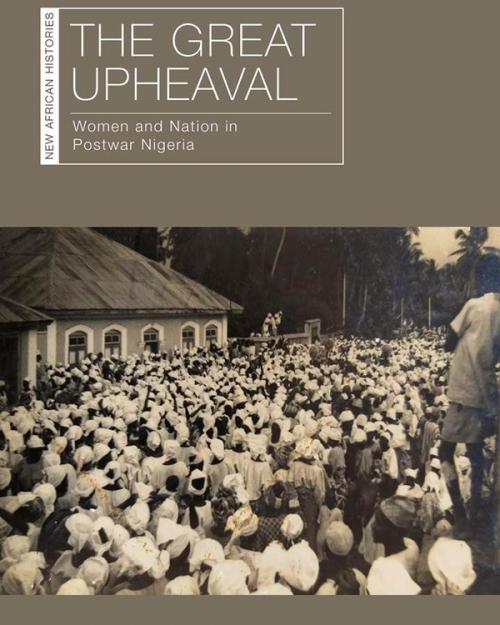

The years immediately following World War II were pivotal for women in Nigeria. Spurred by economic hardship and an unfair tax system, they began to organize in the city of Abeokuta and forge a fresh political vision, for themselves and their nation.

This period is explored by Judith Byfield, professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences, in “The Great Upheaval: Women and Nation in Postwar Nigeria,” published in hardcover and ebook in July by Ohio University Press as part of its New African Histories series. The paperback will be issued in November.

Byfield discussed the book with the Chronicle.

Question: Your book highlights the central – yet underappreciated – role that gender played in Nigeria’s nationalist movement. Given that women’s contributions are so often left out of historical narratives, what kinds of sources did you draw from for your research?

Answer: I was very fortunate because I had access to a wide range of primary sources including: the personal papers of the president of the Abeokuta Women’s Union, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (Special Collections – Kenneth Dike Library, University of Ibadan); records of the local governing council in Abeokuta; files from the colonial government’s Chief Secretary’s Office as well as Colonial Office files in London; newspapers; and memoirs including that of Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. I also interviewed a number of people who had observed the protests, two of Mrs. Ransome-Kuti’s children, as well as former colonial officials.

Q: What effect has the marginalization of women had on Nigeria’s political history?

A: The marginalization of women has resulted in histories that reinforce the idea that politics was men’s work and that women held no opinions about the political debates of the day. Nigeria, but more specifically Lagos, had a vibrant newspaper culture and a cursory look at the newspapers of the era reveal that women weighed in on a number of issues.

Q: Why is the town of Abeokuta essential for understanding this history?

A: Abeokuta holds a particularly important place in Nigerian women’s political history because it was the birthplace of the first genuinely national women’s organization, the Nigerian Women’s Union. There were numerous women’s organizations, including economic guilds, religiously affiliated groups and secular elite women’s groups, but most operated within a localized area. However, after the Abeokuta Women’s Union successfully halted the tax increase and forced the Alake, (the paramount ruler) into exile, men and women from across Nigeria asked Ransome-Kuti for assistance in setting up women’s unions. As a result of this tremendous demand, Ransome-Kuti convened the conference in Abeokuta from which the Nigerian Women’s Union emerged.

Q: What effect did World War II have on women in Nigeria?

A: WWII impacted women’s lives in multiple ways. The colonial state took over the economy. The administration froze wages, set the purchase price of agricultural commodities including food, set the price at which women – who dominated internal trade – could sell their produce, established production quotas on certain food items and limited the movement of foods deemed essential commodities. The colonial government did not freeze the price of imports, some of which had become necessities in the local economy. Inflation raged; but traders and farmers could not legally raise prices. Although they often complained that they were forced to sell below the cost of production, they could not get any redress.

Q: How did the threat of taxes impact women?

A: The tax policy across Nigeria was not uniform. In most places, women did not pay taxes directly; wives were incorporated into their husbands’ tax assessment. Abeokuta was one of a few places in Western Nigeria where women paid taxes independently. … Colonial administrations relied heavily on local taxes, and during the war a portion of local revenue was sent to the metropolitan government in the form of a gift – £100,000 in 1940. This meant that colonial officials had to get as much tax revenue from all potential tax payers, at the same time that they controlled prices and wages. Officials gathered as much information as possible about tax payers in order to improve the tax rolls; they increasingly jailed men and women for nonpayment of taxes, and offered little consideration for those who claimed impoverishment. Abeokuta was one of the few places where women were caught in this vise, between the state’s demand for tax revenue and state-controlled prices.

Q: What is most misunderstood, or unknown, about women’s political activism in Nigeria?

A: Most people are unaware of the degree of women’s political and economic engagement. Too often people have assumed that Nigerian women’s activism is new or a result of colonialism. Officials in Nigeria were often caught by surprise when women mobilized to challenge colonial policy. They tended to assume that outside agitators galvanized women. It was hard for them to acknowledge that these women theorized their experiences of colonialism and mobilized social, economic and political resources to challenge the colonial state.

Q: What surprised you most in your research?

A: I was surprised by the sense of fear and foreboding on the part of colonial officials. The memoir written by John Blair, the official tasked with resolving the crisis, revealed how close they were to calling in the army on the women protesters. They wanted to reassert control of Abeokuta, but they were concerned about the optics. They did not want to create martyrs that would add fuel to the nationalist movement.