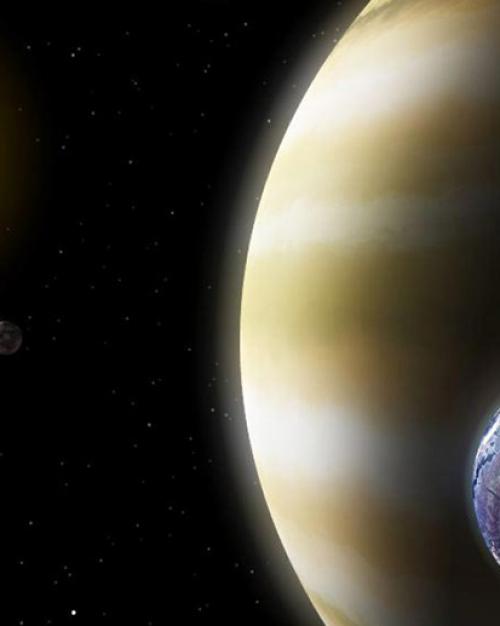

In our solar system – diameter, about 11 billion miles – moons stay relatively close to their home planets. But beyond the stable confines of our cosmic neighborhood, lunar bodies around exoplanets can become castaways and carom across galaxies, according to Cornell astronomers in The Astrophysical Journal.

Colliding and jostling are among the mechanisms that can disrupt the orbits of exoplanet moons, which act like cosmic bumper cars. The scientists found that 80 to 90 percent of the orbits of moons around exoplanets were destabilized.

“Given the high probability of exoplanet moon ejection, there is likely a population of free-floating objects in interstellar space that were born as moons of giant planets,” said lead author Yucian Hong, a Cornell doctoral candidate in astronomy.

This planetary and lunar scrambling occurs often as a result of planet-planet scattering. When a planetary system forms, planets themselves can become close enough to exert gravitational perturbation among themselves, causing erratic, noncircular orbits, said Hong.

With noncircular orbits, the exoplanets can easily cross each other – and when they do, the bodies can deflect off one another. This process happens multiple times until one or more planets – and their moons – get flung out of their home solar system by other planets, ending an extraterrestrial tussle, said Hong.

Close encounters, and the properties of planets and moons, determine the stability of moons, Hong said.

“Among all factors, the planet mass and the initial orbits of moons stand out as clear predictors of a moon’s final outcome, though only in a probabilistic sense,” said Hong, adding that moons with Galilean-like orbits – much like those in our own solar system – have a much higher chance of remaining stable than distant moons.

Other authors of “Innocent Bystanders: Orbital Dynamics of Exomoons During Planet-Planet Scattering,” published in January, are Philip Nicholson, professor of astronomy; Jonathan Lunine, the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences; and Sean Raymond, Université de Bordeaux, France. The research was supported by a NASA grant.