After 360 engine burns, 2.5 million executed commands, 635 gigabytes of gathered data, 162 moon flybys, 4.9 billion miles traveled and 3,948 published papers, NASA’s 20-year Cassini spacecraft ran the last lap of its historic scientific mission Sept. 15.

Cornell students, faculty, researchers and members of the public observed Cassini’s grand finale from the Space Sciences Building early in the morning – the craft racing on fumes – as it went out in a literal blaze of cosmic glory. The project’s science team, which had been meeting at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, saw the plunge from the West Coast.

The room was hushed as Cornellians watched via television JPL monitor the spacecraft’s data return as it dove through Saturn’s atmosphere. The information returning from Cassini arrived in real time, but it took about 83 to 87 minutes to travel the 746 million miles to Earth.

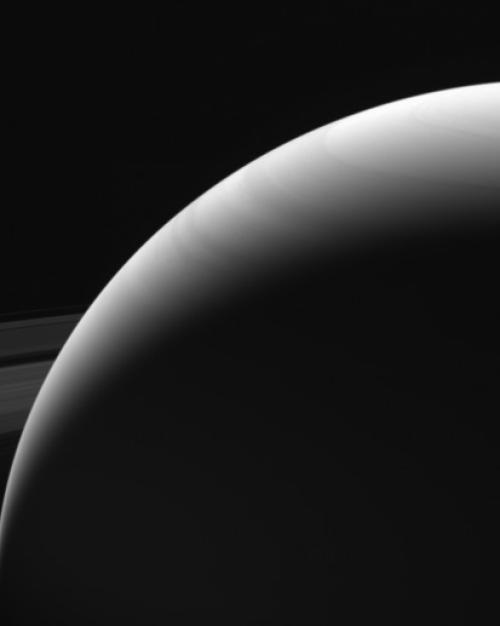

The spacecraft – which ran on 600 watts of power, about half the power of a hair dryer – hit the atmosphere at 77,000 miles per hour, and from the planet’s surface, it likely resembled a meteor.

“The grand finale was bittersweet for me, because as Cassini concludes, so does my professional career as a planetary scientist,” said Joe Burns, Ph.D. ’66, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering and professor of astronomy, who played a prominent role in the mission. “The major part of my research for the past 30 years has been Saturn, the jewel of the planets, and it’s been my good fortune to have participated in this adventure.”

Burns noted that while the mission revealed several surprises, mysteries remain.

“Cassini closes with so many more scientific puzzles,” he said. “They include the origin and the age of the rings; what heats the moon Enceladus; the interaction between the rings and Saturn’s 62 satellites; the variety, the shapes and irregularity of the smallest moons; and the environment of the moon Titan. It will be exciting and so informative for a new generation of researchers to plan the next steps in the scientific exploration of our solar system neighbors.”

JPL controllers noted the deterioration of communications as Cassini’s onboard thrusters struggled to keep the craft pointed toward Earth – still sending data signals, it fought a losing battle against the planet’s atmosphere. The final signal was received on Earth at 7:55 a.m. EDT, some 84 minutes after the doomed spacecraft sent it.

“We have a loss of signal,” said mission control a moment later. The Cornell audience applauded; several boxes of tissues to dry teary eyes were available.

The Cornell celebration was organized by Todd Ansty, a member of the Cassini imaging team; Patricia E. Fernández de Castro Martínez, editor in the Department of Astronomy; Mary Mulvanerton, associate director, Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science; Zoe Ponterio, manager, Spacecraft Planetary Imaging Facility; Jill Tarbell, assistant to the department chair; and Bez Thomas, research support specialist.

Meanwhile, in Pasadena, “Scientists milled for the last few minutes before loss of signal, then all got quiet to watch,” said Jonathan Lunine, the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences. “When it happened, we all applauded Cassini, but it was subdued as we acknowledged the end of the mission, not the beginning.”

Alex Hayes ’03, M.Eng. ’04, assistant professor of astronomy, also in Pasadena, said: “Some folks held hands, others hugged, most stood close in comfortable silence. What struck me most, however, was how people from multiple generations and varied scientific disciplines were completely intermingled. It was a reminder of just how many people have worked on Cassini and how the mission has impacted a significant fraction of the planetary scientist community.”

While waiting for the Cassini signal to stop, Hayes reminded himself the craft had already disintegrated. “We were just watching the bits of data make their way back to Earth,” he said. “While the spacecraft may have ended, the mission and the analysis of data certainly has not.”

Watching Cassini operations team members perform their duties at their consoles for the last time, Lunine said, “Metaphorically, they’d dropped off the science teams ashore at a safe harbor, and they were now scuttling – as they had to do – this great ship of exploration.”

Lunine continued, “Yes, there’s a treasure trove of data to sift through and to understand for years to come, but perhaps for a very long time the Saturn system has gone dark.”

This story also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.