Artists today engage with a world very different from that of their predecessors: globally connected, technologically advanced and highly diverse. In the last fifty years the Western canon has been displaced as the benchmark for “good” and worthwhile art, opening the door to works intended to challenge viewers, rather than simply to aesthetically please.

“It’s an exciting time to be an artist,” says Iftikhar Dadi MA ’01, PhD ’03, associate professor of history of art and interim director of the South Asia Program. “A lot of contemporary art is very provocative, pointing us at things that we need to look at but we don’t always.”

Cornell faculty are engaged both in the creation of contemporary art as well as in its study and curation. Because contemporary art mediums are limited only by the artist’s imagination and have become unbounded by geographical borders, the wide range of cultural expertise at Cornell lends an important depth to the study of contemporary art. Visual artists today even engage with the boundedness of time, in different forms of performance media.

“Art mediates between thought and the world, between intellectual work and politics and society,” says Pedro Erber, associate professor of Romance Studies. “Making art, because of its material aspect, becomes a possible bridge, a way to materialize theory and make it have a presence in the world. When you make something, when you go from thought to a material object, you are dealing with a completely different kind of communication than in academic literature.”

No Easy Answers

“Contemporary art doesn’t give you easy solutions,” says Dadi. “It makes you think in more complex, less instrumental ways and identifies things to which you should be attentive. It offers ways of thinking and experiencing that go beyond established norms, and that’s its value.”

His own work, created with his partner Elizabeth Dadi, is a good example of this. “Efflorescence,” the Dadis’ recent project, uses the language of pop art and commercial signage in a large-scale commentary on sovereignty and the nation-state: the series consists of six giant neon flowers that are industrially fabricated, each the national symbol of a country or region with disputed borders.

Partial view of Efflorescence exhibition

In their giant scale and their graphic industrial character, the works confound expectations as to what delicate flowers should look like. The specific flowers referenced in this series are supposedly sacred national symbols, but grow widely, across nations and even across continents. The works speak to the arbitrariness of nationalism and its borders, but their mesmerizing light and shapes also suggests the seductive power of nationalism, says Dadi.

Photographer Andrew Moisey, postdoctoral associate in history of art, is particularly interested in how big ideas find their way into photographs. His book project, “The Photographic World Picture,” shows how philosophical observations that are impossible to see--for instance, Newtonian mechanics, structuralism, sociobiology, and globalization--became visible in the paintings of Canaletto and the photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher and Andreas Gursky.

“Each of these artists persuade us to see world-structuring forces in the patterns that make up their pictures,” explains Moisey.

Art at the boundaries

Experimentation, with all its risks, is essential to contemporary art and can extend beyond things normally thought of as art. For example, artists in the 50’s and 60’s experimented with money as objects of art; one Japanese artist was arrested for making copies of the 1000 yen note. His legal trouble, says Erber, inspired Japanese artists to reflect on the similarities between art (painting/drawing as a medium) and the production of value with paper money. That reflection inspired Erber to examine the relationship between art and economics.

“I’m looking at and trying to understand to what extent the economy itself has become closer to the way judgment works in the realm of art and aesthetics,” he says. “It’s an attempt to think about economics from the point of view of art rather than the other way around.”

Landscape paintings would seem to be a fairly straightforward art form, yet from an Indigenous perspective, the genre of landscape painting is one of the conceptual and visceral tools of colonization, says Jolene Rickard, associate professor of history of art and director of the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program. “The representation of the land is a central trope in Indigenous thought and visual culture, yet historically, it does not conform to the conventions of art historic painterly or sculptural representations of the landscape. It expresses a very different temporal and philosophical relationship to place.” Suspending the notion of landscape as a painted canvas is appropriate in this context, says Rickard, in which glass chalk beads and blue woolen trade cloth on the bottom corner of a woman’s skirt constitute a Haudenosaunee “landscape.”

The Dadis’ recent Epic Ecologies exhibition in Mumbai challenged a different kind of boundary. As the exhibition text notes, their goal was to address “the distortions created by official narratives—the stories about ourselves and our histories that we are encouraged or compelled to believe by pervasive dominant forces. What alternatives exist to these narratives, how can they be contested?” The exhibition included images of old South Asian melodramatic films photographed from a vintage TV screen. These works suggest a flickering and hallucinatory memory of a modernity that was already fully global by the 1960s.

A 2012 exhibition Dadi co-curated at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, “Lines of Control,” inspired by the Partition of South Asia in 1947, also addressed art at the boundaries. It included 33 international artists and groups grappling with issues that arise when borders are redrawn and new nations are born. “Much of contemporary art ethically critiques our conceptions and practices of modern institutions, such as the nation-state, which were meant to usher us into an enlightened new age, but which can no longer suppress the violent memories of their founding or their inassimilable exclusions and remainders,” wrote Dadi in the exhibition catalog.

Global Art

“Studying modern and contemporary art as a global phenomenon is its own kind of political statement,” says Dadi, “as the history of modern art has traditionally focused on the Western canon almost exclusively.”

Salah Hassan, the Goldwin Smith Professor of African and African Diaspora Art History and Visual Culture, said that when he began his career, “the challenge for me as a so-called non-Western scholar was the entrenched Eurocentrism in majors and assigned textbooks.” It took him ten years to find sponsorship to curate an exhibition of work by the pioneering Sudanese modernist painter Ibrahim el-Salahi (born 1930), now living in Britain. Eventually, the exhibition which was organized by the New York’s Museum for African Art (now renamed the Africa Center), was mounted by the Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates and subsequently shown at The Tate Modern in London, UK, accompanied by a comprehensive book entitled “Ibrahim El Salahi: A Visionary Modernist” (2013).

Says Hassan, "the field of art history itself has moved away from a Eurocentric linear model towards a more global one of studying art movements and artists, and in the process it incorporates new methodologies engendered by imperatives of race, gender, sexualities and other intersectionalities that truly define our world. The field has also moved away from linear narratives of art history that centers on the west towards a more comparativist global approach in the study of modernism and modernity."

In 2014, Associate Professor of History of Art An-yi Pan brought 33 Taiwanese artists together in an exhibition at the Johnson Museum that explored the effects of globalization and the interconnected world. Many of the artists displayed in the exhibition, “Jie (Boundaries): Contemporary Art from Taiwan,” personally experienced the martial law that lifted in 1987, and address local and international politics and major social and environmental concerns in their work.

The river of time

Ananda Cohen Suarez, assistant professor of history of art, has found a kind of contemporary art form in historic murals in Peru. “They’re living monuments,” she explains. “Even though we don’t think of them as contemporary art, they’re still interfacing with a contemporary public. These historical images of past struggles resonate with audiences in the contemporary moment.” Her forthcoming book, “Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes” details her findings.

She’s also looked at contemporary murals, most recently in a course she co-taught with Ella Maria Diaz, assistant professor of English and Latina/o Studies, called Visualizing El Barrio, which concluded with a student-curated exhibition.

Students unveil their exhibition, "Visualizing El Barrio," in Rockefeller Hall. Photo by Jason Koski/University Photography

“Murals originated as a way of empowering communities,” Cohen Suarez says. “I’m interested in understanding how artists of colonial Latin America and the Latino diaspora of the 20th century are both responding to social oppression, and how are they able to express that -- and contest those ideologies -- through the painted image.”

The murals Cohen Suarez encountered when she lived in New York City made her consider their connections to issues of political sovereignty and social change. “It got me thinking: if contemporary people are doing this now and using the painted wall for expression or contestation, can we apply those ideas to the past? Through the research I did in Peru, through archival and historical research I realized that these images which normally we consider to be conservative, Catholic images that are decorating churches, are actually filled with all these subversive symbols and alternative meanings, that I never would have thought these artists had the capacity for, because it seemed like a time that was so distant.

“The struggles of the early 20th century are strikingly and sometimes scarily similar to the struggles of today,” she adds. “The questions don’t seem to go away.”

Dadi, too, has looked beyond the formal art scene. He grew up in Karachi, Pakistan, where there were no art museums and just a few galleries. But there was a great deal of visual motifs to be seen on the city walls, which were covered in graffiti, signage, and posters: commercial, religious, and political. “You have to think more capaciously about culture and art in a place like South Asia,” he says.

María Fernández, associate professor of history of art, works in the history and theory of digital art, Latin American art and the intersections of these fields. In her book “Cosmopolitanism in Mexican Visual Culture” (University of Texas Press, 2014), she investigates how art and architecture in Mexico have reflected power dynamics and forms of violence that were established in the colonial era – before Mexico became independent of Spain in the early 19th century – and have persisted since. The book received the Association for Latin American Art’s 2015 Arvey Book Award.

“I have a thirst for understanding early transitional work but at the same time I’m excited about the contemporary as well,” says Rickard. “Many people who work in non-Western arts are working across time and materials. The field is organizing itself very differently from the periodization of European art.”

Art and Social Justice

“It’s redundant to say art and politics. Art is politics,” says Bill Gaskins, visiting associate professor in the department of art.

For Rickard, a visual historian, artist, and curator interested in the issues of indigeneity within a global context, “the subfield of art and social justice is where my practice fits. I’ve always seen myself at the intersection of how history is visualized and how artists address that space. Artists are turning over our perceptions of reality and see more clearly structures that maintain oppression, structures of dominance that impact populations.”

The Haudenosaunee are leaders in the discussions of resurgence and self-representation of Native Americans today, says Rickard, who is a citizen of the Tuscarora Nation, the sixth nation of the Haudenosaunee. “It’s an interesting time for recognition of indigenous peoples as not domestic dependent populations, which is the way that we’re constructed in the US legal record.” In her work, says Rickard, she’s looking at artists who resist that colonial framing.

One of Rickard’s pieces, which grew out of her interest in indigenous languages, was displayed in the Johnson Museum. The media piece was on naming and the use of the Tuscarora language. In the performance piece, Rickard’s hands braid corn husk (something she learned to do as a child) while her daughter speaks the names of the seven generations of women in their family.

“There’s a moment in indigenous communities, a healing process, being called ‘resurgence’ and a key part of this is the youth and their relationship to language,” explains Rickard.

Erber discovered another kind of connection between art and politics while working on a book about the rise of contemporary art in Brazil and Japan. As he learned how art intervened in politics in the 50’s and 60’s, he was struck by the similarities in how artists in the two countries were thinking about art and society and art and politics.

In an outgrowth of his book project, he’s spending his sabbatical year organizing an exhibition of Japanese art in Brazil, “The Emergence of Contemporary,” that will be shown in Rio de Janeiro and San Paulo this year. The exhibition is timed to coincide with the Summer Olympics in Rio.

“Olympics include a project of modernization being imposed from above,” says Erber. “We saw it in Japan in 1964 and we’re seeing it in Brazil now, with different degrees of success. How artists responded to the transformation of Tokyo in 1964 can resonate in the contemporary moment. Attendees seeing this politically engaged artwork from Japan will recognize its relevance in Rio.”

Bio Art

From the late 20th-century to the present, artists have made art using live entities including plants, animals, cells, tissue cultures and bacteria. They have designed habitats, crops, body organs, created new species and attempted to salvage extinct ones. Some artists also have produced works in traditional media such as painting, sculpture and photography. Some examples of bio art are documented in the Rose Goldsen Archive at Cornell, which is curated by Timothy Murray, the Taylor Family Director of the Society for the Humanities.

“While artists always have imaged and sometimes directly engaged with aspects of the natural world in their art, bio art responds to recent developments in genetics and information technologies. Because of its foundation on the life sciences this art entails significant ethical, social and political dimensions, ideally suited to examination by humanists,” says Fernández, who will be teaching a seminar next year on bio art with Angela Douglas, professor of entomology and molecular biology and genetics.

Intersections: Art & Academics

“I am often surprised by how often scholars, academics, and critics refuse to acknowledge that artists are intellectuals and art is an intellectual project,” says Noliwe Rooks, associate professor of Africana. “We often tend to think about artists as people who are struck by inspiration or just filled with an artistic spirit that has to find a medium. We don’t always acknowledge the training, practice, hard work and most importantly, intellect, required to become an artist. As a result, scholars can often decide to use a piece of art to exemplify a larger point they want to make, as opposed to using art as a theoretical intervention in and of itself.”

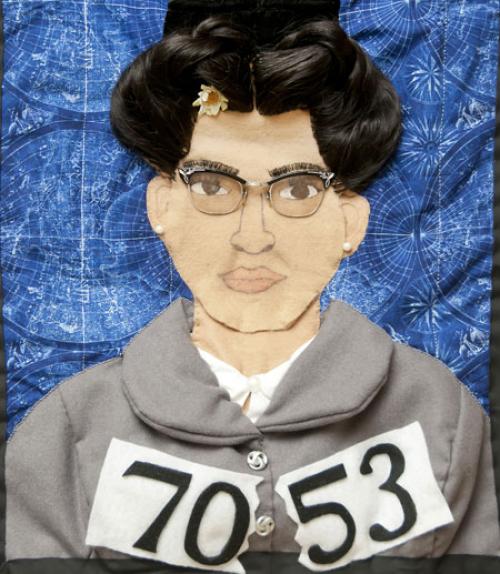

Riché Richardson, associate professor of Africana studies, says that “for a long time I kept my art and my academics in separate compartments, but I’ve been astonished at how frequently the subjects I’m working on in my research are paralleled by subjects I end up making into quilts. In that sense, the processes are dialectical. I’m able to frame similar questions in my art to ones I develop in my research but for a different audience.”

Fifty-eight of Richarson’ quilts were featured in an exhibition the Rosa Parks Museum when the national commemoration of the Selma-to-Montgomery March was held in 2015. Her Rosa Parks quilt is now on permanent display at the museum.

"A Tie, Too?: Malcolm X." Photo by Mickey Welsh

Richardson’s forthcoming book, “Emancipation's Daughters: Re-Imagining the National Body and Black Femininity Beyond Aunt Jemima,” and its explorations of gender, race and the African American south, are paralleled by her work on a series of quilts on the Obamas.

Richardson spends about two years on each quilt, though some of them require five years or more to complete. The level of detail makes them very time consuming; some have collar bones, eyelashes, and fingernails. She uses a three-dimensional approach, with felt providing the foundational fabric and form and incorporating a wide range of materials, including buttons, fruit, beading, jewelry and hats, so that the quilts have a “coming-off-the-page” effect.

“Civil Rights is so central to my work,” says Richardson. “I want people to enjoy my quilts but also to think about the deeper messages there. I want them to think about what art means, to reach within and rediscover or reinforce the artist within themselves.”

Rickard sees her curation similarly. “For me, it’s all about the ideas. I’m looking for ways to connect with people and that’s what art does,” she says. “Curation for me is an intervention, a making of artwork. An exhibit is meant to impact your physical being.”

This feature is part of the New Century for the Humanities "Big Ideas" project to explore broad contemporary themes in the humanities. The New Century for the Humanities is a series of events and projects initiated to celebrate the opening of Klarman Hall, the first building dedicated to the humanities on Cornell's central campus in more than 100 years.