Unlike many stories about technological revolutions and industry disrupters, this one begins in a mall.

Originally from Guyana, South America, Andrea Madho had a successful career as a stockbroker on Wall Street before transitioning to tech-sector public relations and business development.

On this particular shopping trip in 2015, she just wanted to buy clothing that fit.

“Eighty percent of all women’s clothes are actually made for 20% of people,” Madho said. “It was incredibly frustrating for me to be in the middle of a shopping mall, with money in my hand, dozens of stores and thousands of items, and I literally could not buy a dress for my body.”

The source of Madho’s frustration was the fashion industry’s global supply chain, which mass-produces low-quality, often ill-fitting clothing and creates tremendous waste. Madho envisioned a sustainable alternative: custom-fitted clothing from her favorite fashion brands, available within a few days, with styles re-dimensioned for a consumer’s body shape, then cut on a computer numerical control 3D printer. In 2016, Madho and Philip Manning, a mechanical and software engineer and 3D-printing expert, launched a startup, Lab141, with offices in Brooklyn and Syracuse, New York.

They had an original idea. They had industry experience. They just needed the right materials.

“We were inventing an entirely new manufacturing process,” said Manning, the company’s chief technology officer. “As with most entrepreneurs, you solve a problem, but sometimes you don’t even know the full extent of the problem you’re solving.”

In 2018, Lab141 turned to the Cornell Center for Materials Research. CCMR is one of 20 Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers (MRSEC) supported by the National Science Foundation to promote interdisciplinary collaborations that tackle fundamental issues in materials science and engineering.

Founded in 1960, CCMR is one of the longest-running MRSEC initiatives in the nation, addressing a full spectrum of leading-edge materials research in three areas: spin manipulation, photonic materials and atomic membranes. The center offers seed grants to spark interdisciplinary collaborations among faculty members, and provides students the opportunity to train on $30 million of the most innovative technologies in 22,000 square feet of facility space spread across five buildings on Cornell’s Ithaca campus.

CCMR also has an extensive industrial outreach program, backed by Empire State Development’s Division of Science, Technology and Innovation (NYSTAR). Its JumpStart Program helps startups like Lab141 tap into Cornell’s materials expertise.

The companies apply for the program and pay a fee, and CCMR provides matching funds for the semesterlong project. Michèle van de Walle, CCMR’s industrial partnerships director, and John Sinnott, industrial partnerships manager, play matchmaker, pairing companies with faculty members, and sometimes students, who have the research skills to help. With that support, companies can produce innovative discoveries and the proof of concept they need to attract additional funding and investment.

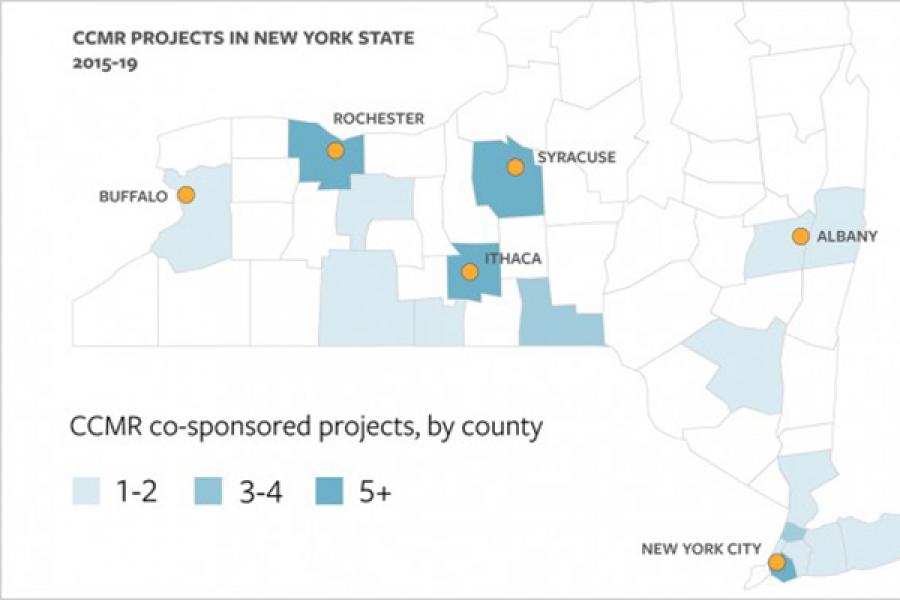

Between 2015 and 2019, CCMR co-sponsored 127 projects with 78 companies, 65 of which were based in New York state. The New York-based projects led to the creation of 61 jobs in the state and $14 million in grants and private funding for the companies.

“New York state’s motivation to fund this industrial outreach program is really entirely based on job creation, industry support. That’s how it should be,” says CCMR Director Frank Wise, M.S. ’86, Ph.D. ’88, the Samuel B. Eckert Professor in the College of Engineering. “We interact with everything from big companies to two-person startups run out of somebody’s garage. For a large company, it’s about the expertise.

“For a small company, having access to a master’s degree student to help with the work, or an extra $5,000, can mean the difference between life and death,” Wise says. “It helps them make it to the next level.”

CCMR connected Lab141 with Anil Netravali, the Jean and Douglas McLean Professor of Fiber Science and Apparel Design in the College of Human Ecology, to explore intelligent bonding technology that could replace the low-cost and often highly exploitive labor of sewing.

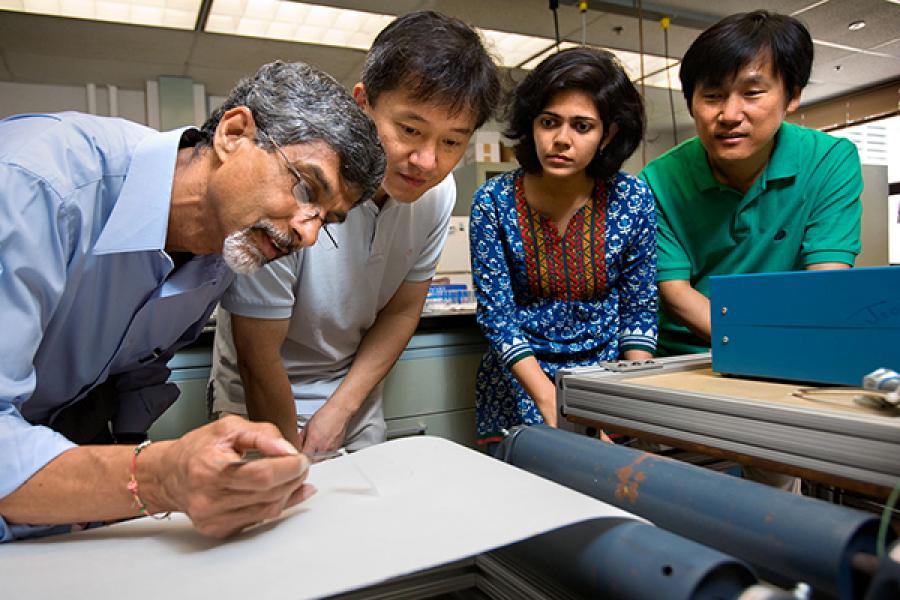

Netravali brought onboard two undergraduates – one in fiber science, the other in apparel design – who worked with Madho and Manning in spring 2018 to examine hundreds of fiber types via microscopy. They also assessed how each type responded to different adhesives, as well as the adhesives’ viscosity, seam strength and washability. The following semester, a new pair of undergrads studied the effects of temperature and time on the joined seams for a second JumpStart project. The team also brainstormed a method of inserting metal sticks into the production process to ensure the seams bonded evenly.

“This came out of our group meeting with the students asking, ‘Hey, if we do that, how will it work? If I do this, what will happen?’ That is the experience the students get: deeper thinking and coming up with viable solutions,” said Netravali, whose own early research developing sustainable, soy protein-based materials received support from CCMR’s seed grant program.

Lab141 is now in talks with commercialization partners. The company has raised angel and grant investments, and in February was one of six finalists in the Tommy Hilfiger Fashion Frontier Challenge. The coronavirus pandemic has interrupted global supply chains for countless industries, and many apparel companies are looking for more sustainable approaches. Lab141 is ready, thanks in part to CCMR.

“We have been so grateful for the full range of relationships that have come out of the CCMR partnership,” Madho said. “You say that you’re a tiny startup that is trying to disrupt the whole global fashion supply chain, and people laugh at you. When you say that you’re working with Cornell University, it gives us instant world-class credibility.”

Making critical connections

For Molecular Glasses, the benefit of working with CCMR is more quantifiable.

The Rochester, New York-based startup has won more than $2 million in grants from government agencies and business incubators from the Department of Energy to the New York State Minority and Women-owned Business Enterprise Investment Fund, thanks to a JumpStart collaboration with Brett Fors, associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“CCMR has a very good process,” said Molecular Glasses CEO Mike Molaire. “A coordinator helps you connect with the right professor, but they don’t stop there. You all meet together several times and there is also follow-up. The process is set up so you know the goals, what you want to accomplish. And after the semester ends, you get exactly what you’re looking for. CCMR came at the right time for us, and that allowed us to get into the DOE testing program, where we really demonstrated the value of our technology.”

Molecular Glasses’ roots run deep in upstate New York. Molaire spent 36 years at Kodak’s research laboratories in Rochester, focusing on materials and formulation research. He left Kodak in 2010 and worked as a consultant for three years. But he missed the problem-solving inherent in materials research. And he had identified a problem he wanted to solve, or at least make profitable: non-crystallizable organic semiconductors for organic light-emitting diode (OLED) applications.

OLED technology was pioneered in the late 1980s by the same division at Kodak where Molaire had worked. OLEDs are self-lighting devices that have a distinct advantage over regular LED technology common in TV and cellphone screens. Since OLEDs emit their own light, they are slimmer and more sustainable, and they produce higher-quality images with greater contrast than liquid-crystal displays. But OLEDs are also expensive to produce and less stable. And if they crystallize, the device will fail.

Molaire had the technical know-how to dig into the issue. But what he didn’t have – and what most high-tech startups often lack – were the necessary tools and facilities.

“If you’re developing software, you can do that in your living room. But if you’re making chemicals, you can’t do that in your garage. You need a lab,” Molaire said. “Kodak had rentable labs, but I couldn’t go there for just a month. You needed to sign a lease for a year or two, and I couldn’t afford it.”

CCMR connected Molaire with Fors, and their initial collaboration was so successful that Molaire applied for a second JumpStart grant the following semester. With Fors’ students, they developed organic semiconducting materials that, when combined, would produce light without crystallizing or shorting out the device.

Molecular Glasses currently has four employees and five U.S. patents with a dozen pending international patent applications. The company is contracting with OLEDWorks, also in Rochester, to build devices and demonstrate their material’s potential to prospective manufacturers.

“It’s a critical time for us. Right now we are engaged with all the big players in the OLED space to prove our technology,” Molaire said. “We’re looking forward to getting our technology fully demonstrated and signing a joint development agreement toward full commercialization in the next two years.”

A colorful discovery

Tobias Hanrath, professor in Cornell’s Smith School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, has been active with CCMR since he arrived at Cornell a dozen years ago. The center is one of the factors that drew him to the university, and he regularly touts it as a recruiting tool to attract prospective faculty and graduate students.

Hanrath’s own research has benefited from interdisciplinary collaborations funded by CCMR seed grants. These projects initiated new research directions and often resulted in significant follow-up funding from external agencies, such as the DOE and NSF.

These collaborations, innovative as they were, did not quite prepare Hanrath for the moment when CCMR contacted him about working on a diagnostic for cow fertility.

“I was laughing,” he says. “I thought they had the wrong guy and maybe they wanted someone in the vet college instead.”

The person behind the diagnostic was not your average startup entrepreneur. Dorothee Goldman has an academic background in animal biology, but she also has a strong interest in public service. As a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal in the late 1960s, she made a colorful discovery: polyphenol pigments, which flowers use to communicate their immune conditions and fertility. The pigments change color in reaction to certain hormones.

In 2006, Goldman launched the Rochester-based Oratel Diagnostics to harness the natural chemistry of these pigments to create rapid, noninvasive, low-cost diagnostic tests to treat endometriosis in women and to help dairy farmers predict successful pregnancy in cows. The dairy application could have important implications for New York state farms that are struggling with a surplus of milk amid the coronavirus pandemic.

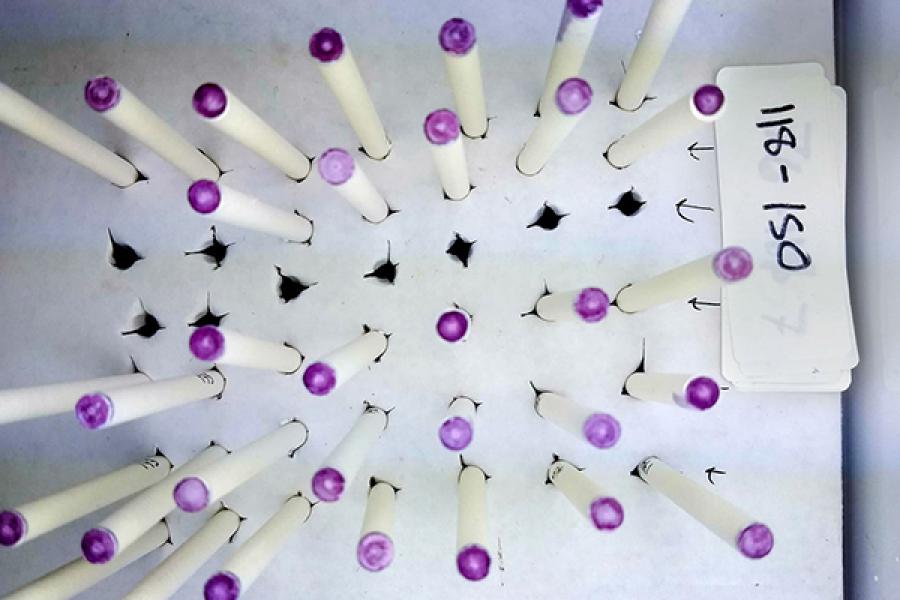

The diagnostics tests, called DaisySTICKs, are essentially popsicle sticks with a small sticker that has been stained with the pigment. A farmer simply lifts a cow’s tail, inserts the stick for a second and then uses a smartphone reader to scan the change in pigment color. The data is beamed via Bluetooth to a cloud server equipped with commercial farm management software.

DaisySTICKs identify the best candidates for successful insemination 18 hours in advance and also help farmers pace calving intervals, leading to more efficient milk production.

The company projects that the tests could boost successful cow pregnancies by 20%; a dairy farm with 1,000 cows could annually save $250,000.

The unique nature of the research required an equally unique array of interdisciplinary collaborations. In the first of three JumpStart projects, in 2010, Goldman connected with Antje Baeumner, professor of biological and environmental engineering, to test how the pigments respond to metals and ions. In 2013, she worked with Uli Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Engineering, to explore the possibility of using nanotechnology to capsulate the pigments. In 2018, Goldman collaborated with Hanrath and student Erica Gardner ’18 to fine-tune the pigment process and explore using nitrogen to package the tests.

Gardner quickly became an expert in what Hanrath calls “MacGyvering”: jury-rigging practical solutions to complicated problems with whatever materials are at hand. She did everything from co-develop an algorithm to identify successful fertile colors to “torture” prototypes to see how they held up when shipped.

Garner and Goldman determined that adding nitrogen to their packaging would be too costly, and instead they could simply include desiccators that would extend the tests’ shelf life from two weeks to almost a year.

Now Oratel has partnered with Biolink AS – a Norwegian company that manufactures the pigments synthetically – to commercialize and produce the diagnostic kits. Together, they have formed a new company, OraCOW, based in Rochester. Nichols Dairy Farm in Addison, New York, is testing the kit. If the tests are successful, additional kits will be sent to farmers in New York and Pennsylvania, and possibly New Zealand, and OraCOW will begin beta trials with potential distributors.

“The most valuable part of getting this technology to commercialization has been the support and help of CCMR,” Goldman says. “There are very few universities that have facilities as broad, with as much range, as Cornell. I’ve been able to work in material science, engineering, chemistry, animal science and food technology, all through CCMR. It really played a critical role.”