Astronomical imagery, a motif central to the study of art history, took on a variety of different meanings and functions among the dominant cultures of the early medieval period.

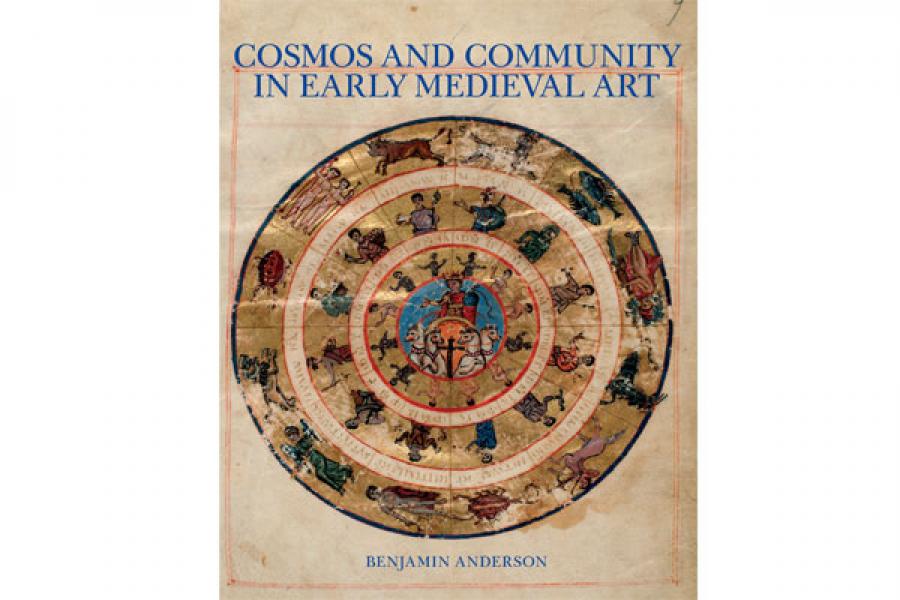

In his new book, “Cosmos and Community in Early Medieval Art,” assistant professor of the history of art and visual studies Benjamin Anderson presents the first comparative study of cosmological art between 700 and 1000 A.D. and details what distinguished such imagery in each of three cultural spheres – the Frankish empire of Western Europe, the Byzantine empire and the Islamic empire in the Middle East. As each of the medieval cultures diverged from their Greco-Roman roots and established their own artistic traditions, cosmic imagery provided continuity, though the images’ local meanings varied widely.

Anderson analyzes the reception of ancient techniques for imaging the cosmos and “uses thrones, tables, mantles, frescoes and manuscripts to show how cosmological motifs informed relationships between individuals – especially the ruling elite – and communities, demonstrating how domestic and global politics informed the production and reception of these depictions,” according to the publisher, Yale University Press.

Anderson first became interested in the topic as a college senior, when he visited the early Islamic site of Qusayr ʿAmra in Jordan.

“The dome of the bathhouse was painted with images of the same constellations that I had learned to identify when I was a kid,” he said, “and I was amazed to realize that a set of images could remain so stable for millennia while being adapted in so many different contexts.”

Benjamin Anderson delivering Cornell University Library "Chat in the Stacks" about "Cosmos and Community"

Anderson’s research for the book was supported by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts of the National Gallery of Art. Its publication was supported by the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association and the International Center of Medieval Art’s Kress Research Grant.

His research interests include the visual and material cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and adjacent regions, with a focus on late antique and Byzantine art and architecture. He also studies the efficacy of forms and nonprofessional interpreters of ancient art, the subject of an edited volume to be published this spring.

His second book, now in progress and tentatively titled “Image as Oracle from Byzantium to the Baroque,” will address the invention and dissemination of a series of prophetic images.

This article originally appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.