In the early 2000s, long before the advent of Spotify and music streaming services, Mukoma Wa Ngugi was a graduate student living in Boston when he went to a late-night party and first heard it. The song playing on the stereo was a kind of blues he couldn’t quite place, sung in a language he didn’t understand. This earworm had a particularly long tail. He thought about it for years afterward.

A decade later, Mukoma applied for a teaching position at Cornell’s College of Arts and Sciences. While doing some light reconnaissance on the A&S faculty, he came across an essay by former professor Dagmawi Woubshet that put a name to the sound that had so entranced him. It was a traditional Ethiopian song called the Tizita.

“I was like, this is the song I’ve been looking for all these years,” said Mukoma, now an associate professor in the Department of Literatures in English. “I spent the next three or four years listening to the same songs over and over again.”

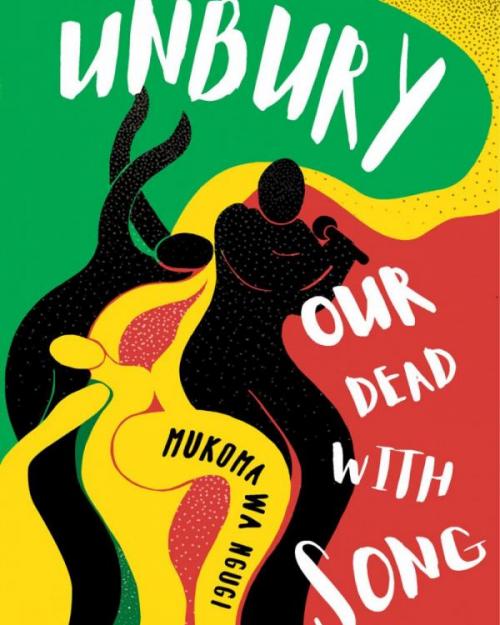

Mukoma channeled that fascination into his fourth novel, “Unbury Our Dead With Song,” which will be published Sept. 21 by Cassava Republic Press. The novel is narrated by a tabloid journalist from Kenya who tracks four Ethiopian musicians vying to see who can sing the best Tizita.

While ostensibly a kind of African blues, the Tizita is more than just a song or genre. The Tizita, for Ethiopians, represents “life itself.” It is “sung for generations, through wars, marriages, deaths, divorces and childbirths,” Mukoma writes. “Every musician, no matter how talented or popular, had to sing the song at least once in their career in order to be respected. … There was a caveat though; a badly done Tizita could destroy a career. … There is no coming back from a bad Tizita.”

Even after working on the novel for several years, Mukoma still finds the ultimate meaning of the Tizita somewhat elusive.

“It’s not a song about love. It’s not about nostalgia. It’s about the soul of the country – like a collective memory that’s bigger than anybody who is listening,” he said. “When I think of the novel, it really is about African beauty, African aesthetics.”

‘Different genres give different answers’

Mukoma’s own body of work also eludes easy summarization. He has published across genres and forms, from literary and detective fiction to poetry to essays and political commentary, even an eight-part radio play. In 2013, New African magazine named Mukoma, who has deep roots in Kenya, one of the 100 most influential Africans, and he has been shortlisted for awards including the Caine Prize for African Writing.

“The reason I work across different genres is, for one, not knowing any better. But the real reason is for African writers, we have to do everything,” he said. “If you’re working in a literary space where a lot of this work has not been done, then you have to do it yourself. We find ourselves having to create these structures. But the more aesthetic reason for me is that different genres give different answers.”

For example, much of his poetry has wrestled with the legacy of the Rwandan genocide and the inexplicable question: “Why does somebody one day wake up and kill their neighbor?”

For Mukoma, the overlap between the historical, the political and the personal is not merely an academic exercise.

He was born in Illinois, but grew up in a village just outside of Nairobi, Kenya, the son of Ngugi wa Thiong’o – a much esteemed Kenyan author and perennial favorite for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“I grew up in a dictatorship where the government was actively trying to undermine – and, really, the word would be ‘terrorize’ – our family,” he said. “My father is a political writer. He was detained, he was sent off into exile. We had the police raiding our house.

“Then I came to the U.S. in 1990. But the thing about being Black in the ’90s is you have Rodney King. You have Amadou Diallo,” Mukoma said. “It wasn’t an escape, if you will, into a blissful exile. That movement itself has shaped everything I do and how I think about the world. Even my teaching.”

This semester Mukoma taught a course about race and the Enlightenment that explored how a movement that purported to advance reason and liberation resulted in colonialism, slavery and racism, all of which continue to reverberate today. Mukoma encourages his students to investigate these kinds of contradictions – not only in others, but in themselves – so that they might expand their thinking beyond ideological consensus.

Mukoma happily admits his own glaring contradiction can be found on the page. While much of his work has focused on the African experience, and he is fluent in Kikuyu, he has never written a full-length book in his own language. He is excited that “Unbury Our Dead With Song” is being simultaneously published in the U.S., the United Kingdom and Kenya – the first time one of his books is being published in his home country.

Over the last decade, Mukoma has been trying to help build a literary ecosystem in which African writing can grow and thrive. In 2014, he and the literary critic Lizzy Attree founded the Mabati Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature as a way to recognize writing and translation in African languages.

The prize, which is primarily supported by the Kenyan steel roofing company Mabati Rolling Mills with contributions from Cornell and Cornell’s Africana Studies Center, has resulted in 10 books of fiction and poetry being published in Africa and has garnered national news coverage there. The award ceremony in 2019 featured Tanzanian president Samia Suluhu Hassan, then the country’s vice president, as a guest of honor. However, getting attention for the prize stateside has been a struggle.

These types of cultural support are difficult to sustain without institutional backing. Another effort that Mukoma launched, the Global South Project, brought together writers and scholars from Africa, Latin America, Asia and underrepresented groups in the West to create a dialogue for a more democratic and egalitarian global culture. But the project collapsed from lack of funding.

“That was a source of frustration,” Mukoma said. “Clearly, this is something that was working. But sometimes in academia there is no thinking beyond a symposium or a conference.”

True to form, Mukoma is currently at work on a variety of projects, including a nonfiction book about Africans, African Americans and the generational trauma of colonization, as well as a television screenplay about the Mau Mau – Kenyans who were conscripted into military service during World War II.

“When most of these stories are told, they are about the colonialists,” he said. “So this is an inversion. This is us now saying, ‘These were the motivations.’ And hopefully it’s a good story.”

Mukoma continues to share that perspective at Cornell. He joined with 24 other faculty members in 2020 to advocate for changing the name of the Department of English to the Department of Literatures in English to better reflect the diverse fields of study. The new name was approved in February.

“Finally, we have a department that’s conscious, in symbolic and structural ways, of the diversity of literature,” he said. “That’s been really, really amazing. The department recognizes the historical moment we are in. Of course, we couldn’t avoid the Black Lives Matter movement, and the pandemic as well. I call them the twin pandemics. They shook us, and we acted, as opposed to retreating into our own corners.”

Read this story in the Cornell Chronicle