This is an episode from the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast's third season, "What Do We Know about Love?" from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about the relationship between humans and love. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the fall semester.

One of the most popular biblical passages read at American weddings today comes from a New Testament letter written by Paul in 1 Corinthians: “love is patient, love is kind, love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude…Love never ends….and now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love.”

Paul’s first-century congregation in Corinth, Greece would have interpreted this passage very differently from the way contemporary American weddings do.

When Paul wrote this text, he was worried about the behavior of a particular congregation of Jesus followers that he’d founded in the middle of the first century. It was a community in turmoil, and Paul was focused on how the members in the community should be treating one another. Lawsuits and incest within the community are just two of the many problems he is trying to address.

There is a sense of urgency to his writings. Paul wrote as a Hellenistic Jew with a new-found conviction that Jesus was the Jewish Messiah and that the apocalyptic end-times were at hand. He based his convictions on his reading of the Torah, the Jewish Scriptures (in their Greek translation) and a solid training in Greek philosophical and cultural ideals.

I think Paul would have been surprised to find his reflections on love read at weddings today, because the key community Paul had in mind was the nascent Christian community, not marital relationships. And the earliest Christian interpreters of Paul would likely not only have been surprised, but deeply concerned by this wedding use.

Christianity emerged in a complex, multi-religious, and diverse cultural milieu. It drew from its Jewish roots a reverence for biblical text — the stories of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, their wives and descendants; the stories of the exodus, conquest of Canaan, and settlement in the land of Israel; and, above all, the beauty of the Psalms, which rendered love and war, despair and beauty in striking poetic form.

Christian interpreters also drew from classical Greek philosophy and culture. What they found there was an emphasis on self-control and emotional restraint. Perhaps more than any other influence, these pushed earliest Christianity toward asceticism and monasticism—giving up bodily pleasures. Early Christians transformed love for a lover or spouse into love for Christ and God, who come to be cast as “the beloved.”

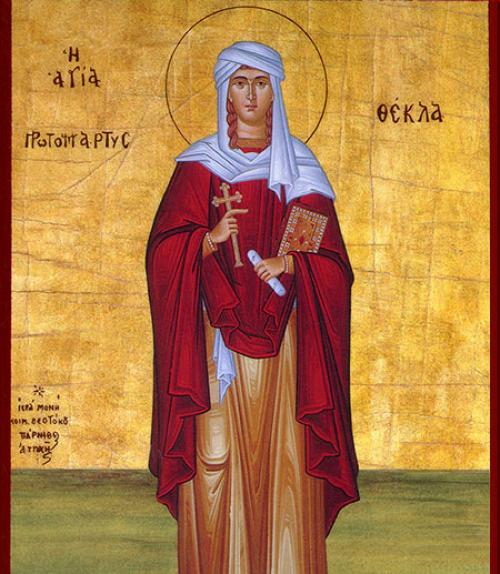

The second-century “Acts of Paul and Thecla,” one of the earliest expansions on the story of Paul, depicts him as a preacher of celibacy. In this work, Paul proclaims blessings on those who have kept their flesh pure, those who renounce the world, and those “who have wives as if they had them not.” Thecla is a young woman about to be married who hears Paul’s teaching in a courtyard as she sits by a window. She is so struck by his words that she decides to break off with her fiancé, follow Paul, and vow celibacy.

Thecla’s actions become emblematic of the ascetic turn in early Christianity. Biblical texts were reimagined, reinterpreted, and reformulated in service of an ascetic project which aimed above all at expressing a love for God by foregoing the love for a human lover. Christ, in this project, became the bridegroom of all those who took a vow of celibacy. Human love became inextricably tied with divine love – and yet we have come full circle in today’s wedding service, once again transforming texts about love to suit our own values and context.