On April 4, 1959, Cornell President Deane W. Malott typed a letter on onion-skin paper to Martin Luther King Jr., inviting him to preach at Sage Chapel. The invitation included a $300 honorarium and accommodations at Willard Straight Hall.

Malott’s letter was the first in a series of formal, gracious correspondence he and King exchanged, comparing schedules and availability. And it was one of many invitations Malott extended to major clergy around the country on behalf of Cornell United Religious Work (CURW).

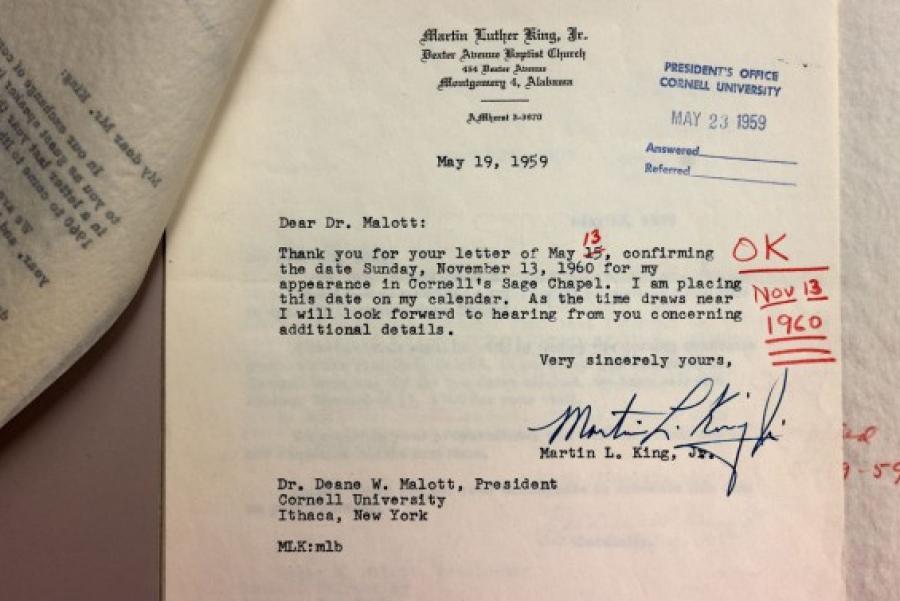

King confirmed his Cornell visit in a letter typed on heavy stationery, with his name and address, in Montgomery, Alabama, printed in Gothic lettering. “Thanks again for your interest,” King wrote. “I look forward with great anticipation to the time that I will be able to appear at Cornell.”

King’s historic visit on Nov. 13, 1960, and a second, on April 14, 1961, came during a period when he was honing ideas that would take center stage at the March on Washington in 1963, says Riché Richardson, professor of Africana studies in the College of Arts and Sciences – ideas that still resonate more than 60 years later.

King used the sacred and the secular to advance civil rights for Black people through nonviolence and civil disobedience, Richardson said. “His ministry was global, and his message has been enduring,” she says. “He really helped us to understand, as he put it, that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

“He was what we might think of as a pioneering public intellectual. And it’s an honor that Cornell was one of those stops that he made, in addition to what else he was doing: leading the civil rights movement in the global arena, always making time to talk to people in communities and on campuses."

‘A pivotal point’

For his first visit, King arrived in Ithaca at 3 a.m. on the Lehigh Valley Railroad, the Cornell Daily Sun reported. Richard Buckles ’61, president of Cornell Student Government, met him at the station and escorted him to his room at Willard Straight Hall, according to the King-Malott letters, now in Cornell University Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

A photo shows King was accompanied by the Rev. Joseph Lowery, a co-founder with King of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); Lowery would later give the benediction at President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009.

King had breakfast at 8:30 a.m. that day at the Statler “Sun Room” with 15 campus student leaders and L. Paul Jaquith, director of CURW. “My earlier letter to you indicated something of the nature of the growing concern on our campus for the problem of inequality of opportunity for the Negro in this country,” Jaquith had written to King prior to the visit.

For nearly two hours at breakfast, King spoke about nonviolent resistance, which he said entails hatred only of mistaken ideas. He said U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy, who had just won the presidency, had grown during the presidential campaign in his understanding of the problems of segregation and would provide badly needed leadership. And King spoke at length about the sit-ins in Atlanta where he was jailed for a week. King said Atlanta was key to desegregating lunch counters throughout the South, saying if the sit-ins worked in Atlanta, the movement would succeed elsewhere, according to the Sun.

“His arrival at Cornell came at a pivotal point in King’s life and in American political and social history,” said Kenneth Clarke, then-director of CURW, in a 2004 Cornell Chronicle article on King’s visits to Cornell. “Just a few weeks prior to King’s visit, John F. Kennedy was elected president by the narrowest margin over Richard Nixon. King’s visit followed Kennedy’s famous phone call to King when he was jailed in Atlanta for taking part in antisegregation sit- ins.”

Kennedy’s risky political gesture swayed many Black people in the South and West to vote for him and influenced the outcome of a close election, Clarke said.

At 11 a.m., King preached at Sage Chapel. His sermon that day, “The Three Dimensions of Life,” is based on Revelations 21:16 from the Bible and was a regular part of his preaching repertoire, one that King adapted to each setting, Clarke said.

King outlined “a complete vision of God” in three dimensions: self-interest, interest in others and love of God. He applied the concept to integration, the Sun reported, “urging those who would try to solve the problem not to forget any one of the dimensions. Specifically, he deplored violence and the spreading of hatred.”

His visit to Cornell was his last appearance in the U.S. before his historic trip to Nigeria, which was celebrating its independence from Great Britain. King left on a 1:05 p.m. flight to Newark and traveled directly to Africa.

‘Moral ends through moral means’

Five months later, King returned to Cornell, on April 14, 1961. This time, he spoke at a fundraiser to an overflowing crowd at Bailey Hall, sponsored by the Cornell Committee Against Segregation and the Ithaca Freedom Walk, according to the Cornell Daily Sun’s April 17, 1961 report.

“It is human dignity which we are struggling for in the South; and we still have a long, long way to go,” King said, according to Sun. He spoke about the progress being made toward equality for Black people in the South, with elimination of the poll tax, an increase in voter registration for Black people and higher wages. But, he said, a rise in Ku Klux Klan activity and the low economic status of Black people were just a few examples of barriers to equality.

He also talked about nonviolence as a solution and “moral ends through moral means,” noting that Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of passive resistance enabled India to win independence from Great Britain. He stressed the need for leadership and support from Northerners, white and Black, saying “lukewarm” liberalism was not needed – but a “genuine, true, ethical liberalism” would help the struggle for equality in the South, the Sun reported.

A crowd of 2,600 people attended. One was Thomas Eisner, the J.G. Shurman Professor of Chemical Ecology, who was well-known for his work with insects and died in 2011.

It was a life-changing moment, Eisner told the Chronicle in 2004.

“I remember hearing King speak in Ithaca, and I was just bowled over,” Eisner said. “I didn’t need persuasion about the devastatingly unfair situation in regard to race relations. But King had the simplest yet most profound way of making a point, and he never wasted a word. His passion, conviction and personal courage inspired and deepened my personal commitment to social justice.”

There are many lessons we can learn by studying King’s legacy, Richardson says.

In Ithaca, his work was carried forward through Dorothy Cotton, the civil rights activist who worked in King’s inner circle as the highest ranking woman in the SCLC. She later became Cornell’s director of student activities from 1982 to 1991. To advance her legacy, the Center for Transformative Action, a Cornell affiliate, established the Dorothy Cotton Institute in 2010 to promote a global community for civil and human rights leadership. Cotton died in 2018.

King visited Ithaca as he was bringing the issues of voting rights to social justice and racial equality to the national stage, Richardson says.

“Dr. King built a crucial foundation for activists to advocate for those issues in the past, but the concerns continue and persist,” she says. “And we have new generations mobilizing to bring about a more just and inclusive society, one that protects civil and human rights.”