In 1788, two ships disappeared in the South Pacific. When they went down, the Boussole and the Astrolabe had been on an expedition commissioned by King Louis XVI, led by French explorer Jean-François de Galup, comte de La Pérouse. Their loss became one of the most widely publicized disasters in French maritime history.

More than two centuries later, contemporary explorers used cutting-edge archeology technology to collect nearly 5,000 objects from the wreckage during eight expeditions between 1996 and 2008. Many of the recovered objects had become agglomerations, accumulating oceanic sedimentation and transforming into new configurations of nature and culture, past and present. Still other artifacts – from on board and elsewhere – tell even more of the story.

When pieced together, especially through objects, “the venture is a testament to the ability of humans to recover what has been lost,” art historian Kelly Presutti writes in “Foul Histories and Forgotten Objects: French Entanglement in the South Pacific,” published in the September 2025 issue of The Art Bulletin. The venture also reveals an extractive tendency within imperial history, she said.

La Pérouse’s expedition was intended to rival those of British explorer Captain James Cook (1727-1779) and to bring the French renown in scientific knowledge, Presutti said. La Pérouse traveled with experts in botany, geology, ornithology, astronomy and other disciplines. The expedition failed in its original aim, but through the visual materials related to the voyage and its wreck, Presutti tells a larger story about the enterprise of empire, finding an emptiness at the heart of it.

“Reading these images and objects oceanically undoes the inevitability of empire, challenges the resolution of disparate moments into a singularly coherent picture, [and] upsets hierarchies of authority and value,” she writes.

Shipwrecks, she writes, change how we read images and objects, pulling them into different timescales, spatial relations and notions of value. Shipwrecks can offer new strategies for the telling of history and art historians are particularly well-positioned to do this.

For art history scholars, agglomerated objects offer a more complicated story of an object and its environment than pieces of art in perfect condition.

“Submerged artifacts react with salt water and mineral particles, both decomposing and accumulating mass, until they are so encrusted in oceanic sediment that they become what I call ‘curious, indissociable configurations of nature and culture, past and present.’ Their forms are the work of both humans and the sea, and they speak to both the time of their making and the time spent underwater,” Presutti said.

She also examines traditional expeditionary objects with the model of the agglomerations in mind, including the maps and drawings created by members of the voyage that made it back to France, as well as paintings, portraits, sculptures and monuments created to commemorate the wreck.

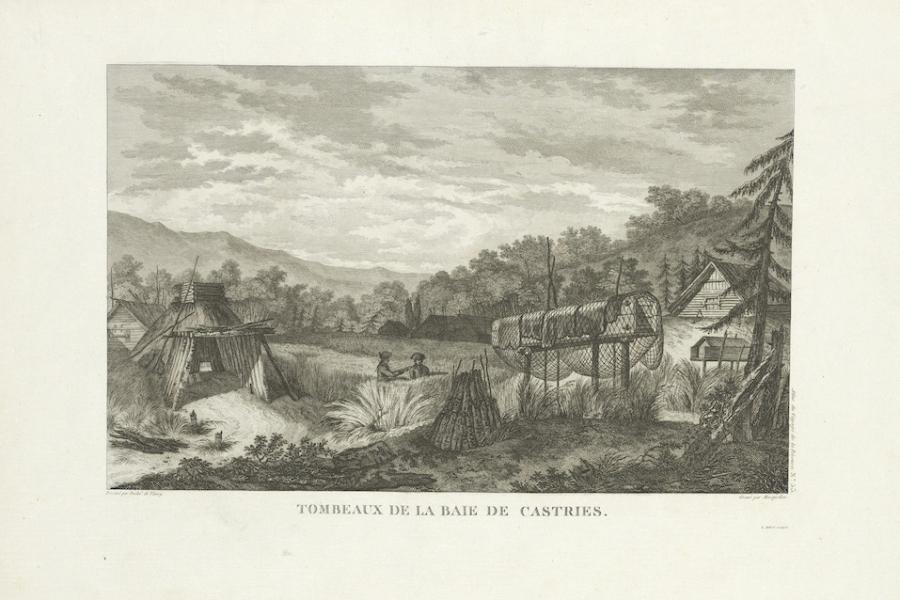

“I was thinking about representation not as the fixed product of human control, but something more fluid, in dialogue with the oceanic circumstances of the expedition itself,” she said. “This led to some speculative interpretations of visual materials that seem to foreshadow disappearance, as in the print of two French sailors wading into a Russian meadow, and also helped me to make sense of the diverse material properties of a series of monuments dedicated to La Pérouse.”

Presutti’s first book was about French landscape, but for her next book, which expands on the themes in this article and looks at the art and object collections of the French navy, she is turning to the sea.

“I wanted to think about what happens when France goes to sea and the security of a territorial identity is displaced by a series of encounters with different places and cultures,” she said. “As scholars look for ways to talk about empire that don’t reproduce its hegemonies, studying shipwrecks offered a way to destabilize seemingly fixed hierarchies and expose moments of weakness, failure and defeat.”

This research was supported by a Research Travel Award from the Society for French Historical Studies and by an Affinito-Stewart Grant from the President’s Council of Cornell Women.