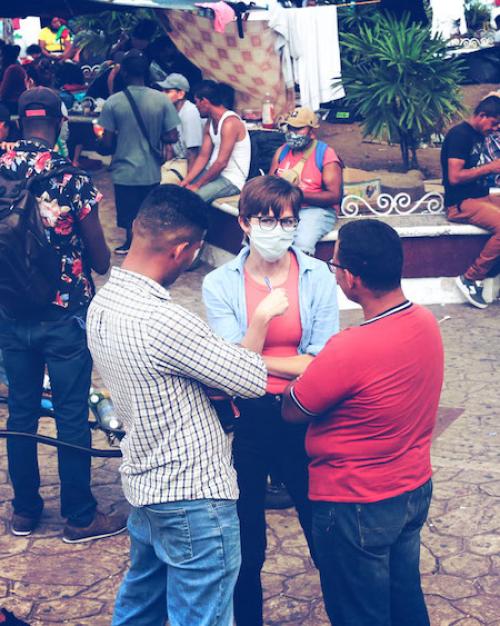

Journalist Molly O’Toole ’09 is spending the next several months following what is believed to be the longest active human migration route on the planet. The project, which she aims to chronicle in a book, will trace the path taken by refugees through South and Central America and Mexico to the U.S. border, stretching approximately 9,000 miles through 10 countries.

“These are people who are coming from all over the world,” she says. “And then, starting in Brazil and Ecuador, they essentially walk or ride—on buses, boats, trains—all the way north. They’re crossing desert countries and thousands of miles along these networks, formal and informal, that span the globe.”

For O’Toole—a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter currently on sabbatical from her job covering immigration and national security for the L.A. Times—exploring this global trek is, in many ways, a way to unite the strands of what has been her life’s work.

Transcending borders

Growing up in San Diego, O’Toole recalls, she could see into Mexico from the hills near her home.

Her early questions—about the seemingly arbitrary line between the two countries, and how lives are shaped simply by being born on one side or the other—sparked a lifelong interest in exploring issues around immigration, refugees, and asylum-seekers, and telling the uniquely human stories behind them.

After majoring in English on the Hill—she began her reporting career at the Daily Sun and interned at Cornell Alumni Magazine—O’Toole earned a dual master’s degree in journalism and international relations at NYU.

She has written for the Washington Post, the Atlantic, the New Republic, Newsweek, Foreign Policy, and the Associated Press—reporting from Central America, West Africa, the Middle East, the Persian Gulf, and South Asia.

She covered the 2016 U.S. presidential election for Foreign Policy and joined the L.A. Times two years later.

In 2020, O’Toole co-won the first Pulitzer for audio journalism for an episode of “This American Life” titled “The Out Crowd,” which investigated the impacts of the Trump Administration’s “remain in Mexico” policy—on both asylum seekers and immigration officials.

She returned to the Hill in fall 2021, spending the semester as the Zubrow Distinguished Visiting Journalist Fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences—teaching an American studies class on U.S. immigration policy and giving several talks. (She also took a Spanish class to bolster her fluency in preparation for her current travels.)

A global journey

O’Toole spoke to Cornellians from Mexico in late January, as she was beginning her research. (The book will be published by a subsidiary of Penguin Random House, likely in 2024.)

She notes that no journalist has yet reported on the full scope of this migration path.

“You have Eritreans, Ethiopians, Cameroonians, Bangladeshis, Indians, Nepalis—people from all over the world—using this route,” she says, “mingling with the groups that most of the American public traditionally associates with immigration: Central Americans and Mexicans.”

O’Toole plans to spotlight individual stories of refugees and asylum-seekers—some of whom are fleeing from what she calls “a deadly cocktail of poverty, climate change, government corruption, and more”—while painting a detailed picture of the interplay of politics, immigration policy, and other factors that have made this harrowing journey so crucial to so many.

The route taken by some migrants—who may originate in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, or Asia—can range from 9,500 to 20,000 miles and last years. Many have leveraged homes or land, or taken on significant debt, to travel via guides and traffickers; they also face the threat of theft, assault, and kidnapping.

“Obviously, I’m coming from a position of immense privilege,” O’Toole says.

“But I’m going to get as close as I can to really understand what people go through along this route, and why they’d put themselves through this for just a chance—and not a high chance—of being able to stay in the U.S.”

As O’Toole notes, climate change—causing droughts and crop failures, and often displacing populations into areas already suffering civil strife—is an increasing factor in human migration patterns.

Additionally, asylum laws—most dating to the post-World War II period and crafted with Europeans in mind—are poorly suited for today’s migration challenges; for example, while many Central Americans are fleeing horrific violence, their cases often don’t fit the laws’ current criteria.

“The right to claim asylum—not to win it, but to claim it—is enshrined in U.S. law,” O’Toole observes. “People may think, ‘This is something we can solve later.’ But there are hundreds of thousands of people on their way along this route, stuck at various points—and there are tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, at the border right now.”