Elora Robeck ’24 couldn’t find rubbing alcohol.

She needed alcohol to preserve the soft-bodied insects she’d collected near her home in Missouri, for her entomology class at Cornell. But it wasn’t included in her box of supplies, because alcohol is too flammable to ship. Her local drug store was all sold out.

So at her professor’s suggestion, she asked her father to buy a bottle of 190-proof Everclear instead.

“We don’t drink in my family, and he had never been in the liquor store before,” said Robeck, who is not yet 21. “He came home and said ‘Let’s not get any more. I don’t want to go back.’”

Robeck is one of five virtual students in Insect Biology, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, who received what the instructor calls a “treasure box” of entomologists’ starter supplies. The box included an insect net, killing jar, pins, collection box and inexpensive digital microscopes. While the Ithaca-based students flip over logs in the woods surrounding campus, remote participants – from Missouri to Miami to Mexico – do the same wherever they are.

“The students are being resourceful in a suboptimal situation,” said the instructor, Cole Gilbert, professor of entomology and the Hays and James M. Clark Director of Undergraduate Biology. “And they like the idea that this class requires them to step away from the computer and go outside.”

The class of 31 students has a hybrid format this semester, with online lectures, in-person labs and insect-finding trips. Normally they’d drive beyond Ithaca, but because it’s hard to social distance in a van, they’re doing their collecting within walking distance of Comstock Hall.

They’ll spend the remainder of the semester studying and identifying their collections in the lab, now spread out into an adjacent room to create more space for social distancing.

“There’s not as much hubbub as usual,” Gilbert said. “They’re distributed, but they’re interacting with each other, they can talk with each other, share ideas, look at each other’s cool specimens.”

From prototyping smart tattoos at home to managing a restaurant via Zoom, Cornellians are adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic this semester with a mixture of creativity, technology and resilience. While minimizing risk and adhering to safety precautions, virtual, in-person and hybrid classes across disciplines are employing innovative ways to leave students with lasting – but safe – educational experiences. And even within the limitations, instructors have found some silver linings, as students learn new lessons in unexpected ways.

“I was worried that this year would be really hard,” Robeck said. “And some of my classes have been hard. But having the online meetings with Dr. Gilbert and chatting with the other students about what kinds of insects we’ve found, how our collections are going, has been really nice. It feels pretty personal, even though we’re so many miles apart.”

Unlearning and relearning

The pandemic has stretched Paul Merrill’s technological skills in ways he never anticipated.

“Group improvisation requires precise, real-time interaction between musicians,” said Merrill, senior lecturer in music and the Gussman Director of Jazz in A&S. “That’s simply not possible with online teaching platforms.”

For his Jazz Combos class, that meant figuring out a way for students to play together, while physically apart.

Merrill spent the summer break building a recording studio equipped with Dante, a networking technology, to provide a safe, in-person, low-latency experience for musicians in multiple classrooms.

A virtual local area network now links microphone- and camera-equipped rooms in Lincoln Hall, where musicians who play wind instruments perform alone. The sound is converted from analog to digital and fed into a studio where Merrill, in the same room as a drummer, bassist and pianist, mixes and captures the signals.

The setup – only possible within the same building – produces a sound delay of around 11 milliseconds for wind instrumentalists. An upcoming equipment upgrade will reduce the delay to less than 3 milliseconds.

“It’s kind of changing the way we rehearse and play together,” Merrill said.

Bassist Stephen Chin ’21 said that while playing this way was initially a “weird shock,” the sessions are the highlight of his week.

“It was kind of unlearning the things we were able to do before, and relearning what we can do now,” Chin said. “One way I communicated was through eye contact and physical cues. So if I wanted someone to follow something that I’m doing, I would stare them down and maybe gesture toward them. But that’s not really possible anymore outside of my one room. So what we do instead is work things out a lot more beforehand, and see if we can let musical cues handle everything.”

For saxophonist Samantha Rubin ’23, playing alone has been challenging – but also helps sharpen her skills.

“Sometimes when I’m playing I’ll make eye contact with other people to make sure I’m doing something right. I look for that affirmation and now I can’t really get that,” she said. “It’s challenging me to develop my ear and my confidence.”

Using this system, the class recently performed a live, virtual composition during StayHomecoming and streamed a live performance as part of the Trustee-Council Annual Meeting.

“If someone throws you a curveball, you have to negotiate it, react to it,” Merrill said. “I think jazz has always done that, historically, as an art form. It moves and stretches and turns and embraces everything going on in the world around it. Hopefully our efforts during the pandemic might be understood as an exploration of that aesthetic. Jazz is alive and well and our students continue to adapt and thrive.”

Preserving a rite of passage

For students in the School of Hotel Administration, Management Night – when their team runs operations at Establishment, a full-service restaurant on the second floor of Statler Hall – is a rite of passage.

“It’s a big night that every hotel student looks forward to for four years,” said Ashleigh Hogan ’21.

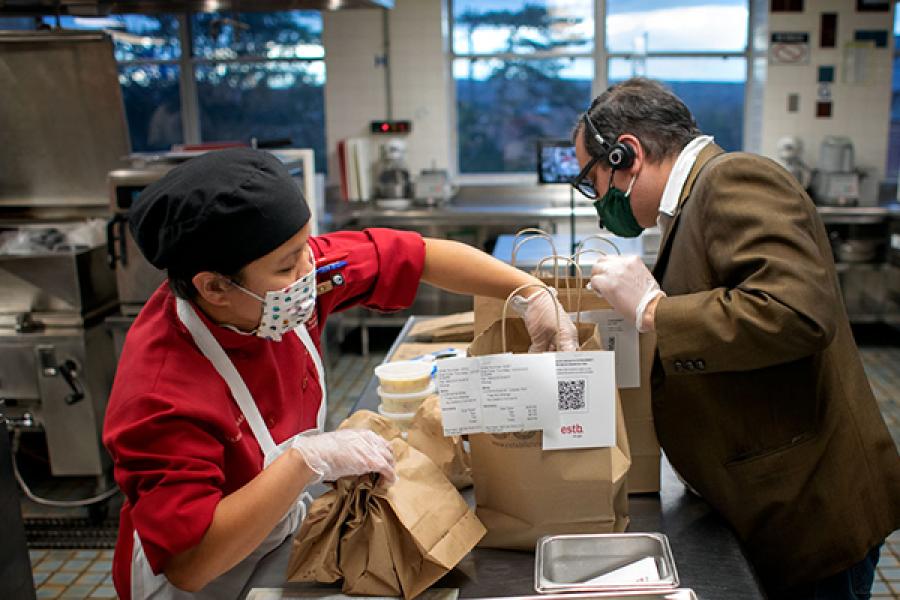

This semester, Hogan and her fellow students in Restaurant Management will still run Establishment, but from afar. They’ve planned recipes and menus, calculated costs and coordinated publicity. On their team’s Management Night, they’ll communicate with the professional staff via Zoom, directing and watching from multiple iPads and cameras around the kitchen.

The course’s instructors, lecturers Lilly Jan, Douglass Miller and Ravinder Kingra, spent the summer transforming the course to virtual, pivoting the restaurant to takeout and contactless pickup, and rearranging and wiring the kitchen so students could survey it from all angles.

“We’ve had to be very creative – we’re teaching a very complex class, and it took a village to do this,” Jan said. “The students still have dry runs, they still have quizzes, they still have to do the menu proposal, they still have to cost supplies, they still have to deal with one another as teammates and navigate the politics of that. So at its core, it has remained very, very similar.”

The shift not only meets campus and state guidelines to keep students and customers safe, it provides the ultimate real-world experience, as the restaurant industry navigates the same challenges.

“We’re showing the students that things change, not everything is going to go your way,” Miller said. “You figure it out, you move on, you grow and improve on it.”

For Hogan and her teammates, that meant choosing dishes that would package and travel well – New England-style food including clam chowder and lobster rolls – and using social media and word-of-mouth to raise awareness. Instead of cooking themselves, they wrote very detailed instructions for the chefs that forced them to think carefully through every step.

“It’s very different from what we’ve seen our older peers go through,” Hogan said. “But the world is changing so much right now, and this is very topical and very representative of what’s happening at real restaurants. So it’s definitely a good experience, and I’m glad we can still implement some of our own ideas.”

The adaptations are only the latest evolution for Establishment, which has changed names and styles many times over the decades.

“This course has an amazingly rich history at our school,” said Alex Susskind, professor of food and beverage management and associate dean for academic affairs at SHA. “If you talk to any Hotelie, they remember it. And that’s why I think it’s so vibrant – because it’s so adaptable. It has to be, in order to give our students a state-of-the-art instruction in this domain. If it doesn’t reflect what’s going on in the real world, we’re not doing our job.”

‘You always put in an arm’

For some instructors, the challenges of social distancing dovetailed with their research and teaching goals. Cindy Hsin-Liu Kao, assistant professor of design and environmental analysis in the College of Human Ecology, aims to use common materials to design wearable tech and smart tattoos – adhesives that are glued to the skin and send signals to devices.

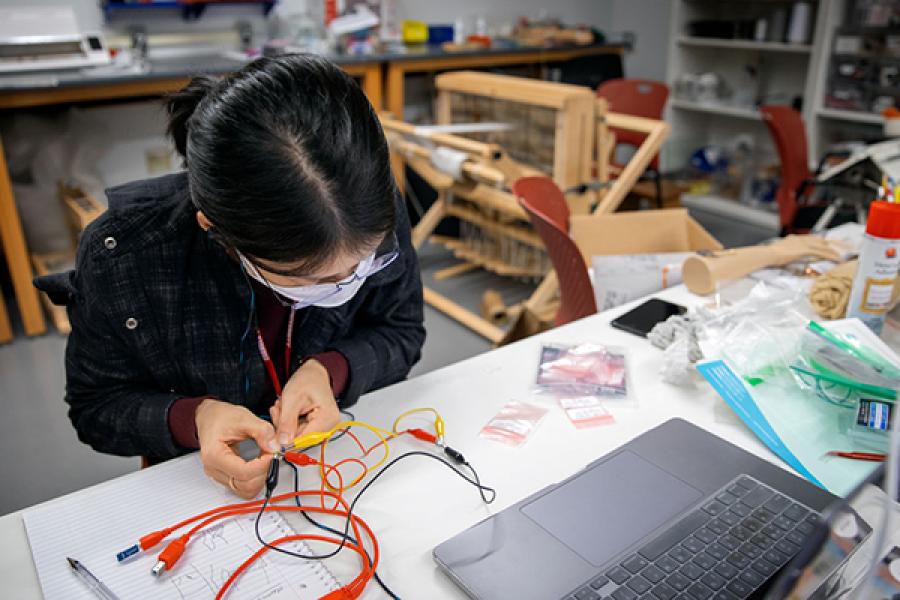

Preparing at-home kits for graduate students in her new class, Future Body Craft, offered the perfect opportunity to do just that.

“My lab is really interested in using everyday materials, and practices that are highly inspired by craft and adapted in an interesting way, so people can actually do this from their homes,” Kao said. “That’s what’s enabling us to run this course. It’s impossible to let students access clean rooms, but because these items are made from pretty accessible tools and materials, we were able to build this kit and ship it to them.”

The kit includes more than 30 items for prototyping, including gold leaf, temporary tattoo paper, embroidery stabilizer, copper wire, conductive thread and tape, several types of batteries, LEDs, small microcontrollers and a mannequin arm.

“You always put in an arm,” Kao said. “For students to prototype they need the mannequin arm to put the tattoo on, see how it works.”

The first half of the course included labs via Zoom, where the students used their kits for a series of exercises, such as creating an LED tattoo using conductive fabric tape. In the second half, they’ll design and build their own prototypes.

“For students to be able to actually make these interfaces, integrate the technology and really understand how it works, they need to be able to practice building them,” Kao said. “What’s really important is the materiality.”

While Kao faced the challenge of developing a brand-new class amid COVID-19 restrictions, many other instructors had to adapt existing classes that rely heavily on lab work and face-to-face collaboration.

Mechatronics, a junior-level mechanical engineering course, normally culminates in a popular event where robots – each built by a group of three students – compete against each other to perform a task.

Some elements of the class couldn’t be preserved in a mostly online format, said the instructor, Hadas Kress-Gazit, associate professor in the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. There won’t be a competition, and the students, who will now be working independently instead of in groups, won’t create full-fledged robots.

But using a mailed-home kit of supplies including an oscilloscope, Arduino board, microprocessor, batteries and breadboards, students will design and build their own devices with motors, circuits and sensors.

Though the projects will be different, Kress-Gazit said, there are some advantages.

“Before, in groups of three, you could get by without ever touching an oscilloscope, for example, because someone else in your group knew how to work with it,” she said. “Now they have to do everything, which is great in terms of learning outcomes. As challenging as it can be to build circuits, they’re all going to have to learn how to do it.”

Rising together as a community

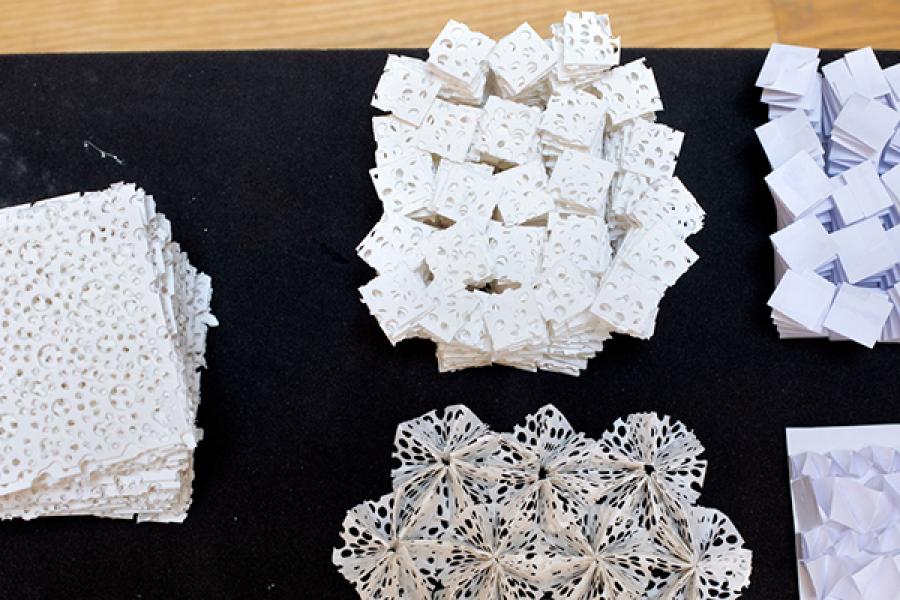

Whether they’re in Milstein Hall, quarantining in the Statler Hotel or home in China, students have access to paper.

“No matter where you are, you can fold a piece of paper and design with it,” said Felix Heisel, assistant professor of architecture, who co-teaches First Year Design Studio in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning with Sasa Zivkovic, assistant professor of architecture, and teaching assistants Elias Bennett, Isa Branas, Oonagh Davis, Iris Xiaoxue Ma and Todd Petrie.

“For architects, paper is an essential medium to transport the ideas,” Zivkovic said, “but it is much, much more this semester because it is also the resource we’re using to build with.”

Instructors designed the class in two-week blocks of nonsequential content, so it would be easy to adjust to sudden changes. To encourage creativity and ease stress, they decided to strike the lowest grade and double the highest grade when calculating each student’s average. The college’s IT department developed “Zoom Booms” with cameras, directional microphones and speakers, so remote students can participate and communicate with others as they work.

“The biggest loss of this new setting is that the learning experience from student to student is so restricted,” Heisel said. “They learn as much from each other as they learn from us.”

To help, instructors created a class Tumblr page where students post images three times a week.

“By scrolling through that page, you can see how this whole group of students is rising together as a community,” Zivkovic said. “On the Tumblr, it doesn’t matter if you’re in person or online, because you’re represented there the same way as everyone else.”

Projects have included designs inspired by a live, socially distanced dance performance on the Arts Quad, in collaboration with students of Jumay Ruth Chu, senior lecturer of performance and media arts in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). The performance was photographed from several angles, recorded by a drone and streamed live on Zoom, so virtual students could experience it as fully as possible.

The architecture students first drew sketches, followed by more accurate drawings and finally built a three-dimensional paper object, all representing the dance or the space between the dancers. The goal, Heisel said, was to understand and question the changing spatial qualities between two bodies in architecture.

“The new technical layer and the recordings actually allowed our students to continuously develop their drawings even after the performance ended,” he said, “resulting in pretty amazing three-dimensional representations.”

Dave Winterstein contributed to this story.