This is an episode in the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about what it means to be human in the twenty-first century. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the fall.

Ours is the age of science. To understand what it means to be human in our time, we look to medicine and technology, neuroscience and genetics.

Ours is also the age of faith in science – what’s called scientism – and it’s not making us happy. In America, one in four women is taking an antidepressant drug. One in seven men do. We are giving drugs to schoolchildren. And we are growing sensationally overweight, to sizes and in numbers never before seen.

For all of this, we blame our brains or genes rather than our lives or ourselves, and we look to science to explain or fix our problems.

The ancient world had very different ways of looking at mental distress. Some philosophers saw what we call “mental illness” as a social and ethical issue: You could fix problems in your life, they thought, once you accepted responsibility for them.

The Epicureans, for example, attributed spiritual anguish to the universal fear of death with the cure being exercise of mind and body – and talk therapy. This was a very popular idea for a very long time, but it’s mostly been forgotten today.

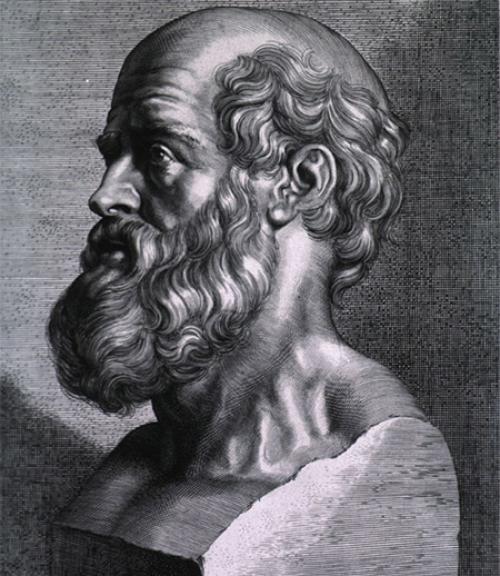

And before them, in the fifth century B.C., Hippocrates had also introduced a medical model, based on the belief that mental illness was a brain disease caused by an imbalance in the humors. Hippocratic healers sought to correct these alleged imbalances through the use of psychotropic drugs like hellebore, forcibly administered if need be, and temporary confinement.

Today we attribute mental distress to alleged chemical imbalances in the body and we seek to correct them with drugs that we call medicines. It’s striking that the ancient medical view, which was decisively discarded in the 19th century, has quietly returned to dominate Western thought.

The value of studying the past is that it unsettles our faith in our own norms. People have not always believed what we believe, and maybe we’re wrong. Ancient literature prompts us to ask whether we should explore alternatives to our current presumptions and prejudices. What if we returned to ancient literature to understand mental distress as a matter of ethics and responsibility? What if we saw our anxiety and fear as signs of spiritual anguish rather than neurologic misfirings? We are no happier than our forebears, and perhaps we are much less so. And so the ancients may be the very voices we need to free us to think differently—and more productively—about what it means to be human in the 21st century.

More "What Makes Us Human" podcasts are available on iTunes and Soundcloud.